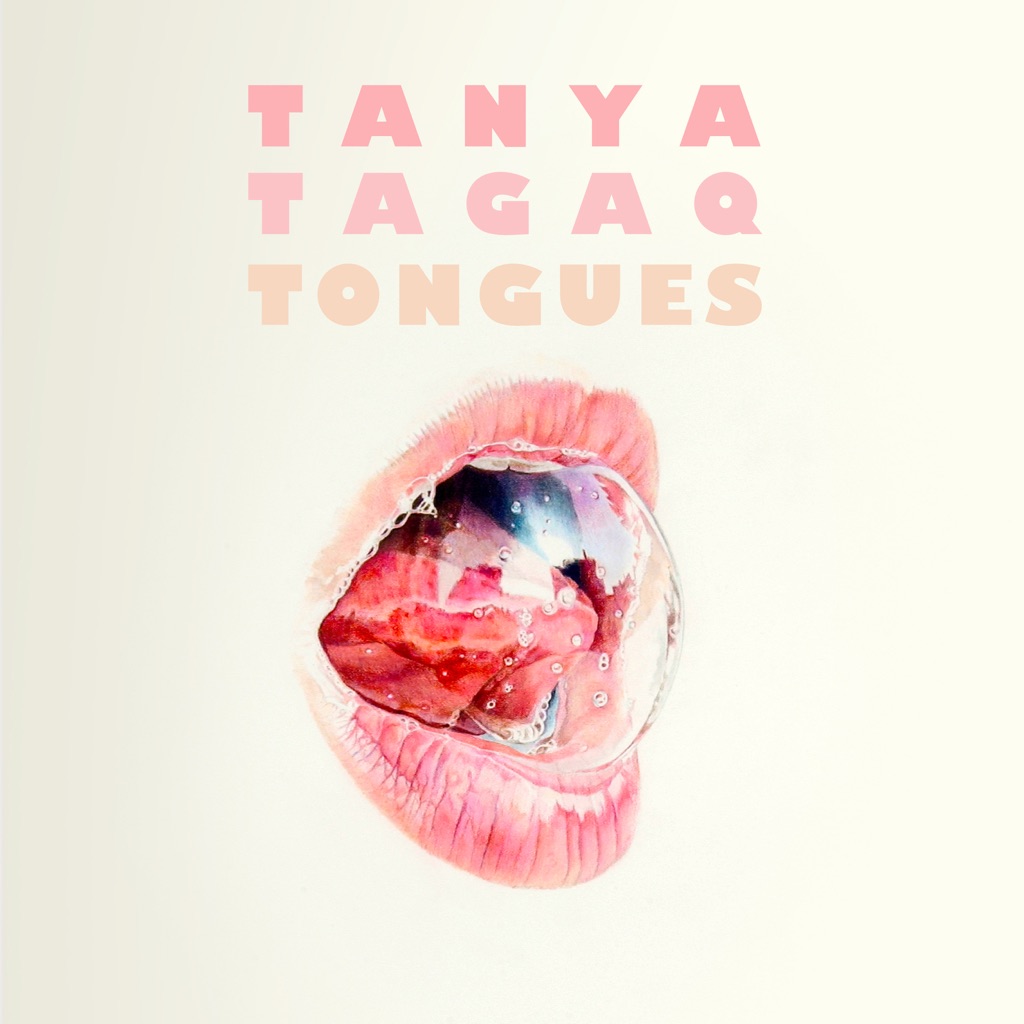

Tongues

Over the course of her career, Tanya Tagaq has committed herself to the cathartic and, at times, deeply uncomfortable process of transforming horror into healing. On past records and in her harrowing live performances, the artist from Cambridge Bay (Iqaluktuuttiaq), Nunavut, has deployed the Inuk tradition of throat-singing to viscerally personify the trauma she’s experienced—sexual abuse, Canada’s genocidal residential school system, the environmental degradation of her homeland—and used her guttural growls to summon a sound not unlike free jazz or metal. But where 2016’s *Retribution* occasionally framed its impressionistic improvisations with spoken-word commentary, *Tongues*, Tagaq’s fifth studio album, fully embraces the narrative form, as she unleashes her signature screams more strategically in service of poems recited from her 2018 novel/magical-realist memoir *Split Tooth*. And while her longtime bandmates Jesse Zubot (violin) and Jean Martin (percussion) make return appearances, Tagaq’s musical DNA has been radically altered by producer Saul Williams and mixer Gonjasufi, who re-situate her graphic, bloodlusty treatises on colonialism, survival, and motherhood in a claustrophobic collage of icy electronics and queasy bass frequencies. “With improvisation, there isn\'t such a cerebral idea or solid concept in the interpretation,” Tagaq tells Apple Music, “but with \[spoken\] word, it\'s very concise and it guides you down a river as opposed to floating in an ocean. I didn\'t know \[my book and my music\] could live together, but when I was recording the audiobook for *Split Tooth*, I was thinking, \'Wow, this is nice and everything…but there\'s no music!\' So I thought, \'How about instead of just reading it, I express it.’” Here, Tagaq provides a track-by-track guide to speaking in *Tongues*. **“In Me”** “I wanted to start by showing my peacock feathers! I wrote this poem out of frustration with vegan activists trolling Indigenous people—there\'s this idea that because we hunt and live off the land, we\'re somehow cruel, or at a lower level of living, when in actuality, it’s a very higher power to be living in harmony with your habitat without polluting your land. The land is still the boss where I\'m from—we have to obey it. So we have a close kinship with animals, and the vegan activists don\'t understand how much we love and cherish other life forms. \'In Me\' became this narrative about skinning an animal—particularly a seal—and how, when you consume a fresh animal, you are eating the energy from the sun. It\'s this idea that you are eating more than your meat. If you eat very sick animals that were raised very unhappily in these giant slaughterhouses full of chemicals and antibiotics, you\'re eating that animal\'s pain and fear and suffering. But when you\'re a really good hunter, and you kill an animal with one shot, and they never knew you were there, their meat is calm, so when you eat them, you\'re eating that, too. ‘In Me’ is about the intimacy in processing an animal and what you glean from it. It\'s about liberating people from this idea that we are somehow doing wrong.” **“Tongues”** “This is a pretty simple, straightforward song: You had all these kids sent to residential schools who then had their language beaten out of them. I, myself, lost my language, and I\'m reclaiming it: I\'m taking Inuktitut lessons now and I\'ve been working on brushing up on my Inuktitut. And I just want to eradicate the shame around that. Canada\'s pushing for Inuktitut to become an official language. I think it\'s time that Canada starts recognizing more than just the colonial languages as official languages.” **“Colonizer”** “I used to do live concerts set to the \[1922\] film *Nanook of the North* by Robert Flaherty, and there are points in the movie where the camera and the actors set it up to show a naivete \[in the Inuit\] where there might not have been. So I loved to sing \'colonizer!\' over that part. But the reason I really wanted to put this out as a song is because Canadians have really got it in their heads that these atrocities \[against Indigenous people\] happened in the past and there\'s nothing to be done about it now. And really, it\'s happening right now, right this second—it never stopped. Every single person needs to wake up and realize their part in that. Often, complacency is what makes room for more violence. There\'s this really false narrative of Canada being this nice place with maple syrup. Yeah, that\'s great and everything, but really, whose land is your house on? So \'Colonizer\' is saying: \'No, you\'re guilty—yes, you! Do something about it!\'” **“Teeth Agape”** “In Canada, the foster \'care\' system—quote-unquote—is the modern version of the residential school program. So I just wanted to say: Enough with taking our children. This isn\'t allowed anymore.” **“Birth”** “I tend to start with a wide-scale general idea, and then a smaller idea, and then a very specific idea. So, \'Birth\' can refer to a birth of a new idea. It can be about the stopping of abuse, because then you are birthing non-abuse. It can be about the end of something, or the beginning of something. But if you want to talk just about childbirth, I really liked the dilation part; the pushing and ripping was not so great. I was very loud in both of my births. And I just remember my mom looking at me, judging me, like, ‘You made noise?\' Because that\'s how tough a lot of Inuit are—there are stories of Inuit women giving birth and being back up and running an hour later. But it\'s dangerous when you\'re giving birth—you are walking the line between life and death, and I really wanted to acknowledge it.” **“I Forgive Me”** “When you\'re abused as a child, you really carry a lot of shame, and anger and fear, and it\'s something that permeates your whole life. So being able to forgive yourself and move past that shame is really crucial. And I find a lot of people are just suffering in silence with these things. I\'m so tired of us not reaching out to each other and supporting each other and understanding that so many of us have gone through these types of things. So I just wanted to say it\'s important to work on forgiving yourself. And it\'s important to open up and talk about it. It\'s part of the healing process. It\'s part of prevention. It was hard for me to make the song and put it out, but I thought about all those other people out there feeling like I do, and how maybe it could help somebody to connect with themselves or forgive themselves—and also simultaneously shame people that are doing this shit. I actually now see the song as quite light, because it\'s shining light where it needs to be shone.” **“Nuclear”** “I was really missing the electricity of the concerts, so there are a few pieces on the album that I wanted to reflect that breakneck urgency that happens in the shows. It gets very, very intense and it grows and grows into a dome and then bursts. And I thought that it was important to have that experience without lyrics on some of the songs, just to make sure the record represents the full breadth of what we do.” **“Do Not Fear Love”** “There\'s an arc to the album, and \'Do Not Fear Love\' is about recognizing the struggle to remain vulnerable after you\'ve been hurt, and learning to trust people, and not going so far into your pain that you begin to close doors that can offer you love. You need to learn to remain open and continue to accept it, even though you\'re hurt. If you open up, it\'s there for you. It\'s an active process. I read somewhere that when you get scurvy, all your scars open up for lack of vitamin C. A scar is actually an active process—it\'s being made. So I think it\'s an active process to clear the path to allow love in, and that\'s something you have to keep an eagle eye on.” **“Earth Monster”** “I wrote this for my \[daughter\] Naia. She\'s 18 now; I think I wrote this on her sixth birthday. Within the intimacy of motherhood, you\'re so close with your children that you can\'t help but have them see your flaws. And as much as we love them, and as much as we want to be perfect for them, they will see our mistakes. This is life and I\'ll celebrate you and do my best to take care of you, but I\'m a seed in the wind when it comes to having control and making things perfect for my child. You cannot do that. The thing about parenthood I find interesting is that when you shield your child from too much, and they eventually go to face the world, the world is so harsh. So you don\'t want to shield your child from life itself—there has to be some sort of acceptance or a better balance between how we communicate with our children. I think it\'s very important that children are able to be children and not live under the oppression of gross adults—yes, they should remain innocent. But should a mother and father never quarrel in front of their child? I think that\'s strange—so your child will not know how to fight? Your child will not know how to say the things they need? Sometimes, I think that bad can be good.”

Vivifying scenes from her debut novel, the Inuk experimentalist and throat-singer marries fiery condemnations of oppression with tender words of protection for future generations.

Inuk musician, author, painter, activist and mother Tanya Tagaq was not raised on the several-thousand-year-old art of throat singing. After...

Tanya Tagaq's album Tongues comes straight at you and doesn't let go. It's a remarkable, difficult work from the Canadian-Inuk artist