Parallel Play

After the 30-track onslaught of 2007’s *Never Hear the End of It*, this Canadian quartet comes back here with the more traditional 13-track *Parallel Play*. Sloan, however, have become less a band than a recording and performing vehicle for its four members\' songwriting forays. Drummer Andrew Scott played all the instruments for his four diverse contributions that include the hit and run aggression of “Emergency 911,” while lead guitarist Patrick Pentland used the other members sparingly. But despite arriving from four different initiation points, the music comes together as a psychedelic pastiche, with guitar riffs and waves of keyboard aiming for straight pop (“Believe In Me”) or trippy late-‘60s type experiments. (Pentland’s “The Other Side” segues perfectly into Scott’s “Down in the Basement,” which flows seamlessly into guitarist Jay Ferguson’s piano-based pop tune “If I Could Change Your Mind.”) Sloan sound as if they’ve emerged from the era of the Beatles’ *Magical Mystery Tour* and the Zombies’ *Odessey and Oracle* with the variety and loose approach of the Beatles’ *White Album* clearly on their minds.

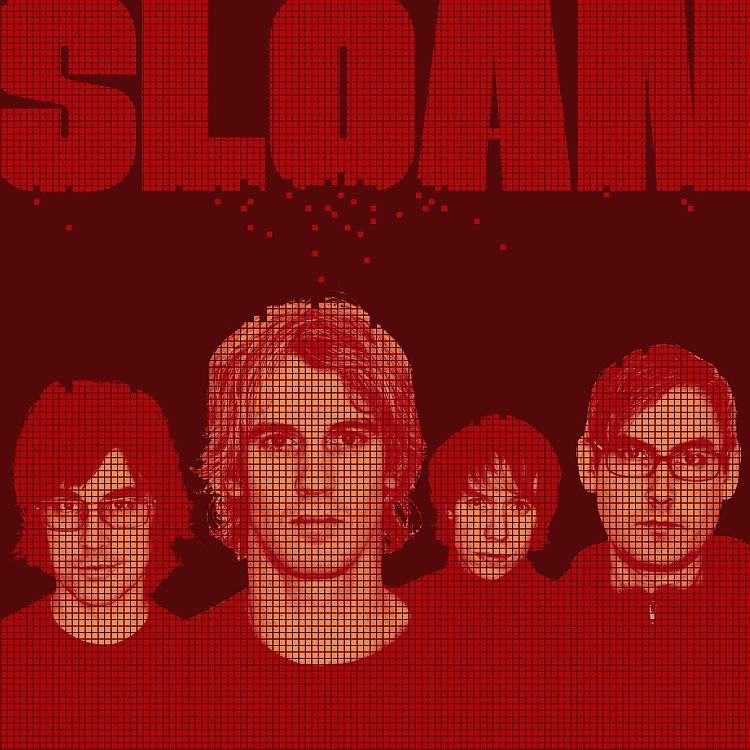

This past winter, when Sloan stepped out of the bone-wracking cold of their native Toronto and into the studio to record their latest album Parallel Play, band members Jay Ferguson, Chris Murphy, Patrick Pentland and Andrew Scott had heard only three of the songs that would soon comprise the album. This fact was not a result of a bad case of writers block or even an ill timed Pro Tools meltdown, but the symptom of Sloan’s unique creative process. Unlike practically every band on the planet, Sloan boasts four songwriters who each contribute more or less equal numbers of songs to their studio works. Parallel Play is no exception. Following the 30-track epic that is Never Hear the End of It, the guys in Sloan have, for the time being, toned down their now legendary creative output. For their latest album, Sloan’s members each contributed three songs (except for Andrew who clocks in at four). For most bands, four distinct creative visions – and egos – would almost certainly mean eminent disaster. But for Sloan it’s the only way to fly. Here, the differences in process, influences, and taste that would fracture a lesser band are the very reason the band functions. Patrick Pentland offers this explanation, “I think we create better separately than when we try to do it together. Some times collaboration works, but we’re such different people, and all of us are capable song writers and producers, that it doesn’t make sense to try to force the band to adhere to some preconceived idea of the typical rock band architecture.” The level of control the songwriters exert over their songs varies within the band, with some members tapping other members to play various instruments on their respective compositions, or like Andrew Scott, playing all the instruments themselves. “I play all the instruments on my songs for expediency’s sake and because I am very picky about what gets played and how on ‘tape.’“ More on the laissez-faire side of things is Chris Murphy, “My strengths are song structures and maybe melodies. My weakness is riffs. I am at the mercy of others to come up with riffs.” Patrick rides the fence, writing alone and calling on others when the time is right, “I tend to work on my own, and get people in the band to contribute if I need them to. I don’t play drums so, unless I use a loop, I get Andrew or Chris to play the drums for me. I’m a fan of Chris’ bass playing, so I usually have him play bass, although I ended up playing bass on two of my songs on this one. I tend to play all the guitar parts on my songs.” Despite the protectiveness some members of Sloan feel toward their own material, in the end the resulting song or album comes about in a decidedly collaborative, decidedly Canadian way. “Everyone has to sign off on everything,” says Pentland. Disagreements are dealt with in much the same manner. “We never fight. We just stew. Aren’t the best bands the ones that are founded in passive aggressiveness? If this is true then we are truly the best band ever,” quips Murphy. The diversity in the individual creative processes within the band translates to diversity on tape. Jay Ferguson explains it this way, “I’m glad that our band magically fell into place that way. I think it has helped us last for 17 yrs and sets us apart from most other groups. Sometimes we get criticized for continually making unfocused compilation records, but I like albums to have diversity even if you don’t get into everything right off the bat there’s always something new to go back for on the next listen. ‘The White Album’ forever.” Despite releasing a staggering 43 songs in just over a year, the four-headed power pop monster that is Sloan shows no signs of slowing down. Parallel Play certainly doesn’t find the well dry as Patrick points out defiantly, “There are no shortages of songs in the Sloan future. We could make another album right now.” Fine by us Sloan, fine by us.

The latest from veteran power-poppers Sloan, Parallel Play, is in a strange position of being a follow-up to a breakthrough album-- 2006's ambitious Never Hear the End of It-- that never really broke through.

Relatively hot on the heels of Sloan's exhaustive (and somewhat exhausting) 30-song epic Never Hear The End Of It comes a leaner but no less comprehensive survey of power-pop sounds past and slightly less past, Parallel Play. "If you believe that everybody needs to shake it loose, then everyone will rock and everybody…

Last year's Never Hear the End of It breathed some much-needed life back into the great Canadian power-pop band Sloan, who had gone a bit stale and...