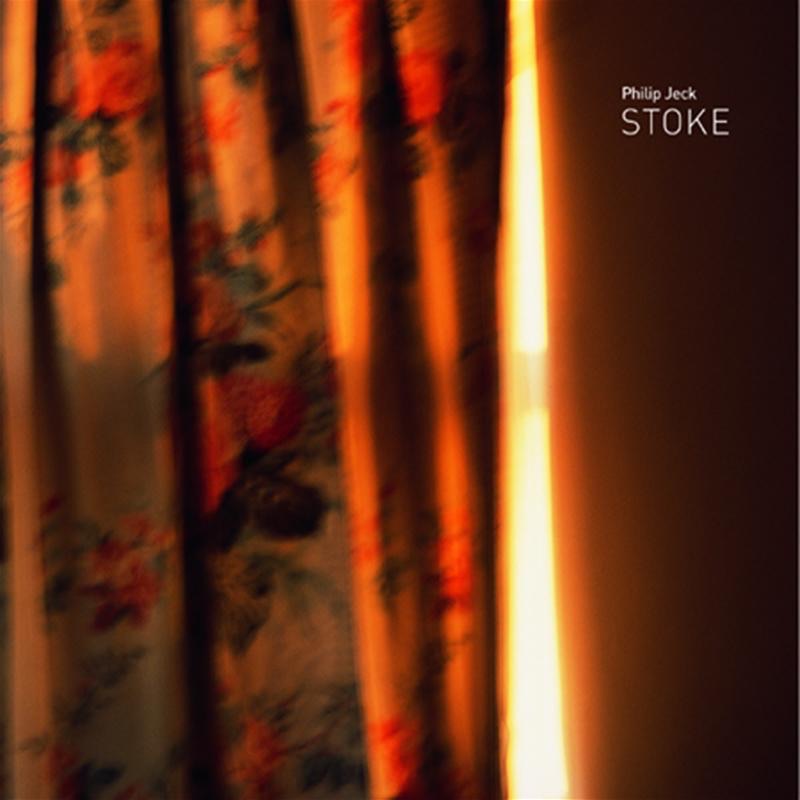

Stoke

With its acrobatic athleticism and penchant for charming gimmicks, in all likelihood HipHop will indefinitely dominate the field of turntablism. Even record-spinning abstractionists like Christian Marclay and Martin Tetrault, who may not always share HipHop's necessity for the beat, put on flashy demonstrations that engage the machismo of technique, alongside their critically minded recombinations of cultural readymades. While Philip Jeck's performances, installations, and recordings have centred around his arsenal of turntables (at last count, he was up to 180 antique Dansette record players, though more normally he performs on two or three, and a minidisc recorder), he isn't terribly interested in the contemporary discourse of turntablism, preferring to coax a haunted impressionism with those tools. However as a calculating improvisor, he shares affinities with the turntable community. Once he is in control of the overall context of the music, he leaves much to the spontaneous reaction towards sound at any given moment. A typical Jeck composition moves at an incredibly lethargic pace through a series of looped drone tracks caught in the infinities of multiple locked grooves. As he prefers to use old records on his antique turntables, the inevitable surface noise crackles into gossamer rhythms of pulsating hiss. Occasionally, Jeck intercedes in his ghostly bricolage with a slowly rotated foreground element - a disembodied voice, a melody, or simply a fragment of non-specific sound - which spirals out of focus through a warm bath of delay. For almost ten years now, Jeck has been developing this methodology, building up to Stoke, his strongest work to date. Its opening passages are on a par with his Vinyl Coda series, with Jeck effortlessly transforming grizzled surface noise into languid atmosphere.But Stoke really gets going with the breathtakingly simple construction of Pax, upon which Jeck overlays an aerated Ambient wash with the time-crawling repetition of a single crescendo from an unknown female blues singer. By downpitching her voice from the intended 78 rpm to 16 rpm, he amplifies its emotional tenor by making her drag out her impassioned declarations of misery far longer than is humanly possibly. The effect is just beautiful. Philip Jeck has always been good, but Stoke makes him great.

Liverpudlian Philip Jeck studied visual art at the Dartington College of Arts in Devon, England. During the early 80s, he ...