Seven Storey Mountain VI

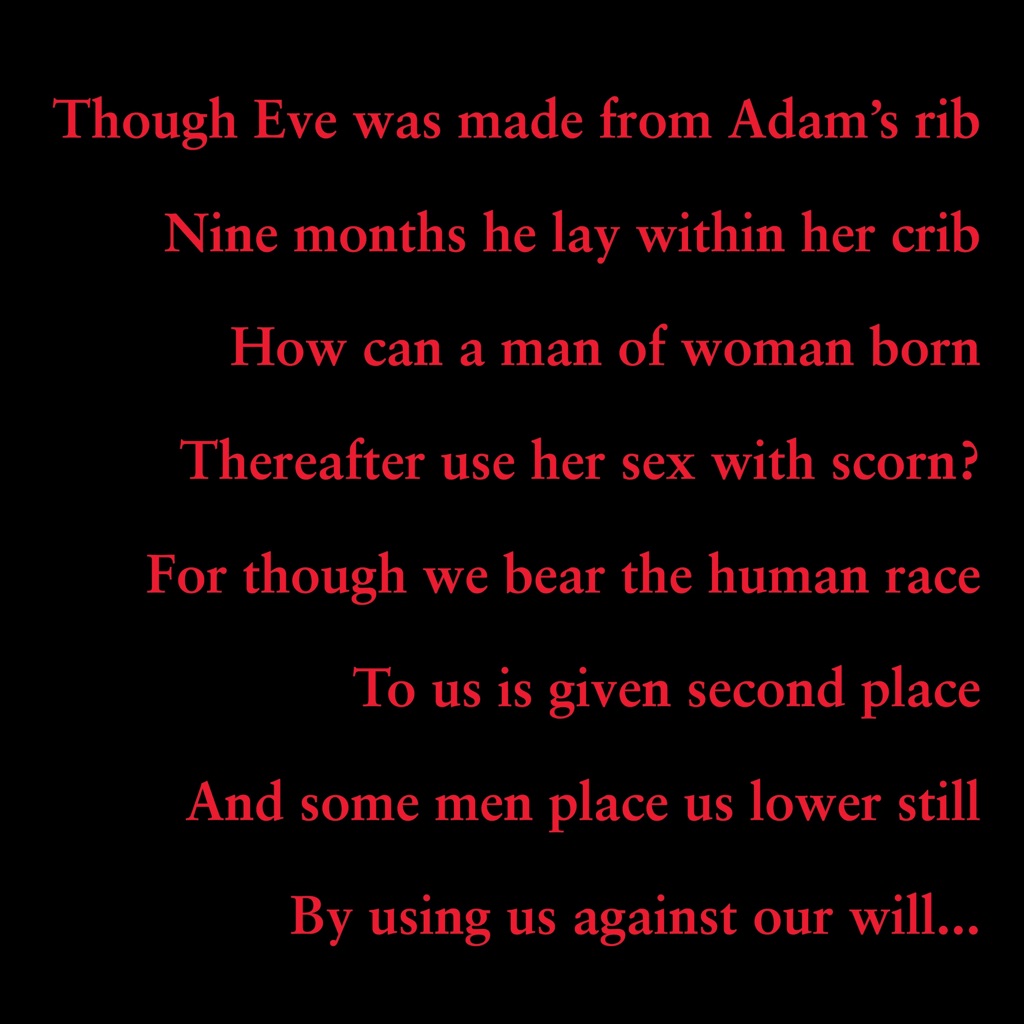

Confrontation Seven Storey Mountain was born of two confrontations. The first is between myself as an active user of machines and the trumpet as the passive machine that I use. Anyone who has practiced an instrument understands this friction and frustration but—given my personal history of being misinformed, partially educated, and brought up off beat—my concept of technical mastery has been less than traditional. Over the years, I’ve tried to understand the trumpet by breaking it down, reconstructing it, screaming into it, whispering near it, doing it (and myself) grievous bodily harm and, as heard on this recording, electrocuting it. I’ve done this, not for novelty, but in hopes of finding its humanity: drawing its technique away from the traditional goal of reproducing the singing voice and toward a technique of sighing, shrieking, and mumbling. The second confrontation is more abstract, but similarly embedded in how the song cycle has unfolded. In the same sense of testing the capabilities of the trumpet-as-machine, I wanted to locate the limits of my own self-as-spirit. These terms are difficult. They carry a certain kind of weight and a feeling of the vaguely religious. This kind of language, as well as the title of this work, culled from Thomas Merton’s autobiographical writing, has overlaid a sense of the “sacred” on the series that should have been disavowed by me long ago, but I’ve yet to find terms that fit SSM as naturally and poetically. Religious dogma holds little interest for me. Instead, what I’m drawn to in Merton’s Seven Storey Mountain—and what I mean by self-as-spirit—is a secular practice of self-questioning and evolution. Ralph Waldo Emerson calls it self-reliance. Seven Storey Mountain is not an attempt to reach a spiritual plane. It is an example of how we take part as humans in the cycle of trying, failing, recognizing, evaluating, regrouping, and trying again; an exercise in the transcendent human process of failure. Mutual Aid Music Building Seven Storey Mountain is a practical process of reverse-engineering. The score is compiled from a dozen differently-articulated sets of instructions to the musicians rather than being preset and articulated in standardized score notation. Each iteration of the cycle begins with a list of individual personalities with different strengths and ways of engaging with music. Some of the musicians don’t want to read traditional notation. Others are more comfortable performing from a score. Still others can do both but are most comfortable somewhere on a spectrum between the two. Seven Storey Mountain presents each musician with a score that is specific to their orientation. They can be free from self-consciousness and redirect all of their energy into an explosion of musical energy. Composing Seven Storey Mountain begins with the pre-recorded sounds that occur simultaneously with the live performance. I take the sound file from the immediately preceding version and strip any sounds from it that feel non-essential. Then, I add elements to this landscape to build a distinct aural topography while still feeling grounded in the earlier versions of the piece. For example, in the middle of SSM6, there are a number of drum samples: a Paul Lytton clip first used in SSM4; a heavily manipulated Chris Corsano loop added to SSM5; and, unique to this version, the overlaid crescendo of Will Guthrie’s “Breaking Bones.” In each sound file since SSM4, some version of the “Lytton Loop”—a short gesture ending in a sustained high bell tone—has been included. Although it has been manipulated in one way or another from one version to the next, that loop has become a through-line in the subsequent pieces. Once finished, this sound file acts as a timeline for the musicians. Their gestures are laid out as timings on a printed temporal score and also correspond to pre-recorded sonic events. The individual parts may be made up of textual instructions with timings, aleatoric notation, jazz chord changes, or fully notated traditional scores. Regardless of the different ways of articulating what, when, and how to add to the performance, the end result is the same: a unified organism of sound—something larger than the individual. To achieve this, we work together. This approach to writing is something I call Mutual Aid Music. And, it has been a central tenet of my compositional and improvisational philosophy for the last ten years in projects from Seven Storey Mountain to Battle Pieces and knknighgh. This form of composing doesn’t aim to reproduce a score coming from a central source (me) but relies on individual and group decision-making as ways of taking musicians out of their preconceived technical or aesthetic languages to create a communal music. Concentrating on how the decisions of each performer affect the overall music (and how those decisions can push the music in unfamiliar directions) asks the player to work beyond their licks and tics, and prods them to express something original and spontaneous to the collective. This approach creates a highly-complex music that is heartbreakingly human in its inevitable failure. Virtuosity is the possibility of collapse. This music demands that the players put themselves in a position of sounding foolish, uncool, bad. It is the willingness to take this risk that raises us, as artists, above mere reproduction. It is terrifying to tempt failure in a solo setting, but the act of throwing yourself off a musical cliff within an ensemble takes on a singular dimension: you have to consider that the people around you are doing the same thing. The best way to avoid failure is to embrace those that jumped with you in an attempt to create something buoyant, something beyond simultaneously hurtling individuals. When it doesn’t work and failure wins, at least the attempt is noble. When it does work (as it does on this recording) the result is a rare form of musical intricacy and intimacy. Ecstaticism, Family, Voice There are a few elements of SSM that are less easily definable, but are vital, and so they should be mentioned. The first is Ecstaticism—a term I may have inadvertently coined in a 2014 interview. Seven Storey Mountain is meant to make you feel something. The live performances of these pieces make people react. They smile, shiver, cry, run for the door to compose their angry emails. The ensemble is there, playing this music, for people to remember that feeling and to take it home with them. We seek to imprint a moment on you. The best part of Seven Storey Mountain is the “We.” Every person who has performed a portion of the cycle has given something to the piece, and some part of the piece has remained with them. Each SSM is written so that everyone can give a little more of themselves than they feel comfortable giving without causing too much strain. Seven Storey Mountain is a chance for the performers to turn themselves inside out in a way that feels safe. Together! Everyone in every ensemble, from the first trio with David Grubbs and Paul Lytton (SSM) to those who have signed on in Germany (SSM5) or Belgium (SSM6) have given something deep and personal. This is especially true of the huge force that came together to perform and record the music on this disc. I call them ‘the family’ with no sense of irony. These are my people and I’m happy to have them in my life. Vibrations When we get ready to rehearse a version of SSM for the first time, I remind the ensemble that our goal is to make the room vibrate in a different way, and to make that room continue to vibrate long after we’re gone. In the past, we’ve achieved this through a variable concoction of volume and a certain feeling of power. When I was preparing this version of Seven Storey Mountain, I found that this kind of energy wasn’t at my fingertips any longer. For the first time, I was angry. I was truly angry as I watched what people do to each other: how some make decisions about peoples’ lives as if they were objects. I was fucking angry watching the government attempt to wrest control of women’s bodies and angry watching Black people be incarcerated and killed with impunity. This anger manifested as the desire to sing loud, but not just with my voice. I didn’t trust my strength alone. Instead, I put my trust in the voices of the women around me. They have a different kind of power that I can’t explain. At the end of the premiere—after much gnashing of teeth and feedback sculpting by the instrumentalists—a choir of twenty-one women led by Megan Schubert stood up in the back rows of a church and, with no amplification, made its walls shake with Peggy Seeger’s words. I hope they are still vibrating and will continue to do so for a long time. To share a room with those voices moved me and, for a moment, I felt whole. - Nate Wooley, June 2020 About the Text The composition of Seven Storey Mountain VI came into focus when I first heard Peggy Seeger’s recording of “Reclaim the Night” from her album Different Therefore Equal. I listened to it over and over again, concentrating on the power of her words and the clarity of her voice. SSM6 uses the first few lines of “Reclaim the Night” as a kind of mantra. The hope was that those leaving the performance—or coming to the end of this recording—would not just remember the melody but also, through its repetition, be able to retain some of Peggy’s words. The phrase “You can’t scare me” that dovetails with the last repetitions of Seeger’s lyrics was inspired by Bobbie McGee’s “Union Maid.” I initially tried to combine the lyrics and melodies of both songs but the result felt too ‘clever’ and drained the power of both songs. Instead, I just set the words, “You can’t scare me”—not an elemental feature of McGee’s original song—to my own melody and let them act as the piece’s final affirmation; the words that I hope the listener takes with them into their daily life. “Reclaim the Night” by Peggy Seeger Though Eve was made from Adam's rib Nine months he lay within her crib How can a man of woman born Thereafter use her sex with scorn? For though we bear the human race To us is given but second place And some men place us lower still By using us against our will If we choose to walk alone For us there is no safety zone If we're attacked we bear the blame They say that we began the game And though you prove your injury The judge may set the rapist free Therefore the victim is to blame Call it nature, but rape's the name Chorus: Reclaim the night and win the day We want the right that should be our own A freedom women have seldom known The right to live, the right to walk alone without fear A husband has his lawful rights Can take his wife whene'er he likes And courts uphold time after time That rape in marriage is no crime The choice is hers and hers alone Submit or lose your kids and home When love becomes a legal claim Call it duty, but rape's the name And if a man should rape a child It's not because his spirit's wild Our system gives the prize to all Who trample on the weak and small When fathers rape, they surely know Their kids have nowhere else to go Try to forget, don't ask us to Forgive them—they know what they do Chorus When exploitation is the norm Rape is found in many forms Lower wages, meaner tasks Poorer schooling, second class We serve our own, and, like the men We serve employers—it follows then That bodies raped is nothing new But just a servant's final due We've raised our voices in the past And this time will not be the last Our bodies' gift is ours to give Not payment for the right to live Since we've outgrown the status quo We claim the right to answer "No!" If without consent he stake a claim Call it rape, for rape's the name Chorus

The first installment of the trumpeter’s ecstatic series to be recorded in a studio is its most beautiful, and somehow the most convincing document of the cycle’s in-person grandeur, too.