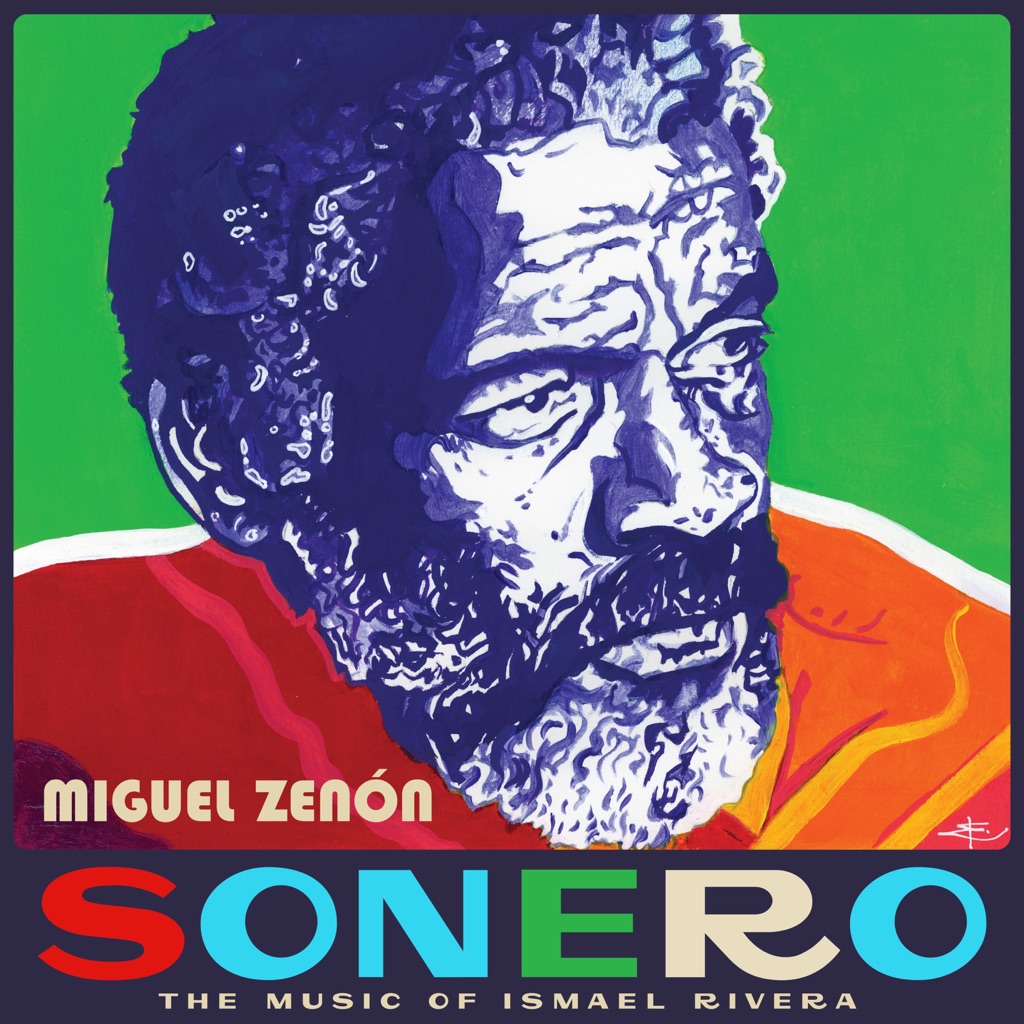

Sonero: The Music of Ismael Rivera

Leading one of the longest-lived and most explosive quartets in jazz today, alto saxophonist and MacArthur Fellow Miguel Zenón has devoted much attention to Puerto Rico’s musical heritage and its meaning for him as a jazz composer. Whether writing original music or reconceiving traditional and popular Puerto Rican idioms like jíbaro and plena, Zenón and the band go at it with passion and spellbinding precision. Pianist Luis Perdomo, bassist Hans Glawischnig, and drummer Henry Cole join Zenón this time for a deep consideration of Ismael Rivera (1931-1987), the eminent salsa singer known affectionately as “Maelo.” We hear him in a sample on the opening track, spliced with the quartet as it orchestrates and reharmonizes what he is singing. And with the stage set so movingly, the group proceeds with epic instrumental reimaginings of “Las Tumbas,” “Las Caras Lindas,” “El Negro Bembón,” and more, steeped in jazz harmony and complex, surging rhythm, with the original melodies and figures used as jumping-off points for development and exposition. Salsa’s sonero (vocal improvisation) tradition dovetails with the grooving modern chamber-jazz aesthetic of Zenón and his compatriots to create music beyond category.

“He wasn’t just one of the guys. For me, he was beyond that,” says Miguel Zenón about Ismael (“Maelo”) Rivera (1931-1987), the subject of his latest project, Sonero: The Music of Ismael Rivera. “He exemplified the highest level of artistry. He was like Bird, Mozart, Einstein, Ali – he was that guy.” Zenón knows something about musical greatness. He’s one of jazz’s most original thinkers, known for his harmonic complexity as well as for being one of the most recognizable alto saxophonists of his generation. His great subject is his homeland of Puerto Rico, and he brings a fresh take on it every time out, combining reverence for cultural tradition with strong compositional chops. No one else’s Puerto Rico – and no one else’s jazz – sounds like Miguel Zenón’s. Sonero might be Miguel Zenón’s strongest album yet, and that’s saying a lot. For his twelfth album as a leader, Zenón and his quartet offer a tribute to a musician who influenced him from childhood: Ismael Rivera, who grew up in Santurce, not far from Zenón’s home turf. Familiarly known as Maelo, he’s a popular hero in Puerto Rico today, even more than 30 years after his death. “When people talk about him, they talk about him as you would about a legendary figure,” says Zenón. On the other side of the Caribbean, in Colombia, Venezuela, and Panamá, he’s as popular as he is in Puerto Rico. But in the wider world, he’s not as well known. “One of my main goals with Sonero,” Zenón says, “is that I want everyone to know about him.” Ismael Rivera’s musical background was in folkloric Afro-Rican music. He grew up together with future bandleader Rafael Cortijo, and became the lead vocalist of Cortijo y Su Combo, with whom he became a household name appearing regularly on the Puerto Rican daily TV El Show del Mediodía in the 1950s. Tutored in the repertoires of bomba and plena by the patriarch Don Rafael Cepeda, the two men stand at the head of a movement that turned those rhythms into contemporary dance-band music, which at the time was mostly in the Cuban style. Rivera had a distinctly Puerto Rican style of soneo, or improvisation. The word comes from son, the Cuban style of music that is the mother form of salsa. The album’s title, Sonero, means the lead singer who improvises melodies and lyrics over the repeating coro. It’s one of the highest forms of artistic performance, calling on the performer to display musical and textual erudition while making people dance. Rivera was known to his fans as El Sonero Mayor – the greatest sonero. Coming from a percussion background, Rivera developed a unique style of singing that used vocal percussion phrases – ¡rucutúc, rucutúc, rucutúc, rucutác! -- to fill out lyrical lines, making for a new level of rhythmic complexity on the part of the singer. “I grew up in salsa circles as a kid,” says Zenon, “and when folks talked about all the great singers – Héctor Lavoe and Cheo Feliciano, Marvin Santiago, Chamaco Ramírez, people like that – they always talked about Maelo in a different way. Rubén Blades talks about Maelo as a revolutionary rhythmic genius. “Putting phrases on top of phrases, like threes over fours, stuff that’s so advanced that as a musician you can say, ‘okay, that’s five, then the four, then it crosses over and meets here’ – but I’m sure he wasn’t thinking about that,” Zenón says. “He was just thinking about the way he felt it. But what he felt was so advanced and so ahead of his time that it was really transcendent. So a lot of the elements that I used to write these charts were things that were inspired by what he was doing rhythmically when he improvised.” “But, says Zenón, “Sonero to me doesn’t only mean an improviser. It exemplifies a persona. It’s someone who embodies the genre. I’m attracted to complexity, but in this case it’s complexity on top of a foundation of folklore and just plain grit. It was all there,” he continues. “His timbre, his voice, the way he dealt with lyrics as an improviser and on top of that his rhythmic genius.” Zenón’s albums are conceived as integral works to an extraordinary degree. He’s been bringing out new full-length projects year after year, and his hyper-virtuosic quartet does hard roadwork playing around the world. On Sonero, the group captures the spirit of Maelo – but through its own distinctive lens. The album has the easily identifiable sound of the fully developed Miguel Zenón Quartet, which has remained with the same membership for fifteen years – an astounding stability in the world of jazz. They play a personalized jazz in their own unique style, collectively created under Zenón’s direction and built on the foundation of their easy musical communication. The group’s unity was on display when they premiered the music from Sonero in a stunning residency at the Village Vanguard in March 2019. “Luis and Hans and Henry – we all have a specific connection to this music,” Zenón said. “There’s a connection to it that goes beyond the page. It’s a personal thing. Like Luis, for example -- he’s a salsa head even more than I am. He grew up with this music. When we play the arrangements I’m sure he feels what I feel. He hears those songs and he knows where the source is coming from.” While the pieces included in Sonero are Zenón’s arrangements of other composers’ tunes, they’re so fully elaborated into large-scale works that they feel like his compositions. Listeners may recall his arrangement of Maelo’s signature Bobby-Capó-composed soliloquy “Incomprendido” that lit up the quartet’s groundbreaking Alma Adentro: The Puerto Rican Songbook (2011), an album which correctly treated standards by Puerto Rico’s greatest popular composers as part of the jazz repertoire. Sonero brings a similar approach, featuring versions of tunes by some of the same canonical composers from the repertoire of Ismael Rivera. Some of the selections on Sonero are key tunes from Rivera’s repertoire: “Quítate de la Vía, Perico,” Rivera’s early hit with Cortijo, begins with an accelerating train rhythm; the upbeat feel of Bobby Capó’s “El Negro Bembón,” belies its lyric about the tragedy of a Black man murdered for having big lips; Catalino “Tite” Curet Alonso’s Black-is-beautiful anthem “Las Caras Lindas” – one of Maelo’s signature tunes, covered by many artists; and “El Nazareno,” about his religious experience in the procession of the Black Christ in Portobelo, Panamá, where he was a regular pilgrim. Others are less obvious choices – “Las Tumbas” (The Tombs), for example, with its lyrics about Rivera’s experience in prison; “Colobó,” about the pleasures of living in Loíza Aldea, Puerto Rico’s legendary Black town outside of San Juan where bomba thrives today; and “La Gata Montesa,” a bittersweet bolero-chá about a woman who’s a mountain lion and a “vampiress.” When Miguel Zenón’s quartet gets to stretching the numbers out live, Sonero is a full evening of entertainment. Unheard but not unacknowledged, the stories the lyrics tell float in the heads of the musicians, as they channel the spirit of Ismael Rivera into their own instrumental masterwork.