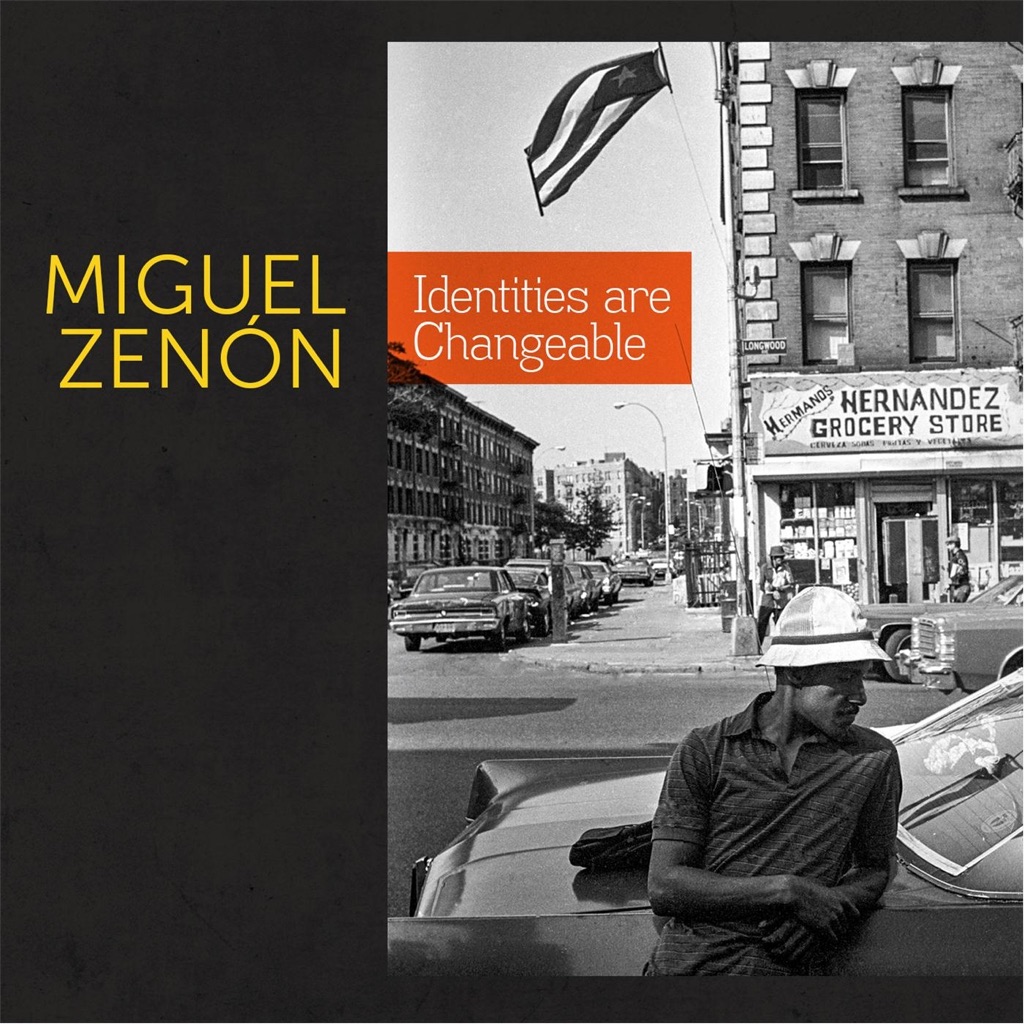

Identities Are Changeable

Puerto Rican alto saxophonist and composer Miguel Zenon has drawn on the music of his homeland over the course of several albums, creating a new and individual form of Latin jazz. On *Identities Are Changeable*, Zenon’s quartet (which includes pianist Luis Perdomo, bassist Hans Glawischnig, and drummer Henry Cole) is joined by a dozen guest horn players. Zenon’s large ensemble writing dazzles with its deft layering of rhythms, textures, and harmony. The compositions wrap around interviews with Puerto Rican New Yorkers sharing their personal histories and ideas about cultural identity.

This is home in the sense that these are the streets I grew up in, this is where my friends are. But that's home because that's where my parents came from and they always talk about that and I dream about it. -- Juan Flores Alto saxophonist and composer Miguel Zenón asked his friends the question he had been asking himself: What does it mean to be Puerto Rican in 21st-century New York City? That was the point of departure for Identities Are Changeable, the startlingly original album by Miguel Zenón, who grew up in the island’s main city of San Juan and came to New York in 1998 to pursue a career in music. Zenón’s experience of moving via the air bridge from the small Antillean island to the landing strip 1600 miles north is something he shares with hundreds of thousands of other “Puerto Rican-New Yorkers.” Puerto Ricans are not immigrants in the United States: for nearly a century – since 1917 – Puerto Ricans have, unlike other natives of Latin America, been US citizens, able to come and go as they please between the island of Puerto Rico and the mainland. When they come north, overwhelmingly they go to New York City. After different waves of migration over the decades – most numerously in the 1950s – about 1.2 million “Puerto Rican-Americans” were living in the greater New York area as of 2012. * * * Miguel Zenón has become one of jazz’s most original thinkers. Today, at the age of 37, he’s one of the best-known alto saxophonists in jazz. The quartet he leads has been working together for more than ten years, building its ensemble coherence on stages all over the world. But Zenón’s more than a great musician and bandleader. One of only a handful of jazz musicians to be chosen for the coveted MacArthur fellowships (in 2008), he’s at the forefront of a new movement that in recent years has brought the composer to a new prominence in jazz. But beyond his facility at writing and playing music, there is a great intellectual subject at the center of Miguel Zenón’s artistic world: the complexity of Puerto Rican culture. Beginning with his third album as a leader, Jíbaro (2005), and continuing with Esta Plena (2009) and Alma Adentro: The Puerto Rican Songbook (2011) (both Grammy-nominated), and Oye!!! Live In Puerto Rico (2013), Miguel Zenón has created a series of thoughtfully framed works that interpret different facets of Puerto Rican culture. Zenón’s Puerto Rico is a bit like Gabriel García Márquez’s Colombia or Gilberto Gil’s Brazil: the highly focused center of an imaginative universe that looks to the world while being rooted at home. It serves a springboard for his personal style: no one else’s Puerto Rico – and no one else’s jazz – sounds like Miguel Zenón’s. Identities Are Changeable, Zenón’s powerful new composition, is a song cycle for large ensemble, with his longtime quartet (Luis Perdomo, piano; Hans Glawischnig, bass; Henry Cole, drums) at the center, incorporating recorded voices from a series of interviews conducted by Zenón. Commissioned as a multi-media work by Montclair State University’s Peak Performances series, it has a multi-media element with audio and video footage from the interviews, complemented by a video installation created by artist David Dempewolf. It’s been performed at such prestigious venues as the New England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall in Boston, The SFJAZZ Center in San Francisco, and Zankel Hall in the Carnegie Hall complex in New York City. The album version of Identities Are Changeable is a labor of love, produced by Miguel Zenón without commercial backing. It will be released November 4, 2014 as only the second title on his personal label, Miel Music. I think more and more people are realizing that you can be more than one cultural self at the same time, and you're at the crossings of those. Rather than being just squarely in one, you'll be at the crossings. -- Juan Flores The core of Identities Are Changeable is a series of English-language interviews Miguel Zenón conducted with seven New Yorkers of Puerto Rican descent. His initial impetus for the project came from reading The Diaspora Strikes Back: Caribeño Tales of Learning and Turning, a book by cultural theorist Juan Flores based on interviews with Puerto Ricans who had returned to the island after living on the mainland. Zenón turned the tables and interviewed Flores, whose insightful commentary grounds Zenón’s finished work. Other interviewees who weave in and out of the musical texture are Miguel Zenón’s sister Patricia Zenón; the young musicians Luqués Curtis and Camilo Molina; actress Sonia Manzano; poet Bonafide Rojas; and family friend Alex Rodríguez. This is speech as music: their recorded voices, speaking off-the-cuff in their own surroundings with the sound of the city around them, tell the story. Writing about it in The Wall Street Journal, jazz journalist Larry Blumenfeld quoted Zenón: "I asked pretty much the same things to everyone," [Zenón] said, "the essential question being 'What does it mean to be Puerto Rican?'" As Mr. Zenón analyzed his footage, themes emerged: Do you speak English or Spanish? How is tradition passed on? Zenón identified key excerpts from the interviews and grouped them into six thematically related clusters: national identity, home, blackness, language, the next generation, and music. As he began writing instrumental music to support the voices, those clusters became six fully elaborated musical movements, plus an intro and outro, making for a 75-minute work of symphonic dimensions. I always thought I was the blackest Puerto Rican. Because I was a Black Panther before I was a Young Lord, because I liked Hendrix before I liked Hector Lavoe. -- Bonafide Rojas Identities Are Changeable showcases Miguel Zenón’s most ambitious instrumental writing yet. It’s scored for a 16-piece large ensemble, consisting of Zenón’s working quartet supplemented by five saxes, four trumpets, and three trombones. If you think you already know what that sounds like, think again: though this pulsating, percolating music is intensely rhythmic, it’s not achieved through the now traditional mambo-style section writing. It’s still Latin, and it’s still jazz, but this sonority – Zenón’s first big-band score – presents a different kind of compositional and orchestrational challenge, and a different kind of polyrhythm. It’s more like modern symphonic writing, with layered multiple meters that give new meaning to the term “harmonic rhythm” as they create a translucent texture. Zenón explains: “all of the compositions explore the idea of multiple rhythmic structures coexisting with each other (e.g., 5 against 7, 3 against 2, 5 against 3).” Drummer Henry Cole has his hands (and feet) full holding down the simultaneous time streams, as does Zenón when he conducts the group live. The players are a selected elite team – hear John Ellis’s tenor solo on “Same Fight,” or Tim Albright’s trombone feature on “First Language.” There’s no way to convey in words the impact of the orchestral effects, but reviewing the Zankel Hall performance for The New York Times, Ben Ratliff writes: “[The] sound and language didn’t directly suggest traditional Puerto Rican music or traditional jazz. Its rhythm was phrased almost completely in stacked or odd meter, with parts of the band shifting into double or half time, and Mr. Zenón’s saxophone darting around the chord changes or resting on top, in long tones. There was drama and momentum in the music’s developing harmonic movement; at times a shift to a new chord felt like an event. All the music was deeply hybridized and original, complex but clear.” It’s all at the service of Zenón’s relentless curiosity, as he writes in the album’s liner notes: When I first came into contact with Puerto Rican communities in this country, I was shocked to meet second and third generation Puerto Ricans who were as connected to the traditions of their parents/grandparents and as proud to be Puerto Rican as the people I knew back home. Where was this sense of pride coming from? What did they consider their first language? Their home? What did it mean to them to be Puerto Rican? What are the elements that help us shape our national identity? If the music doesn’t directly answer these questions, it provides a way into thinking about them. Like Zenón’s other music, it’s about an entire society, but it’s deeply personal.