I Do Play Rock And Roll

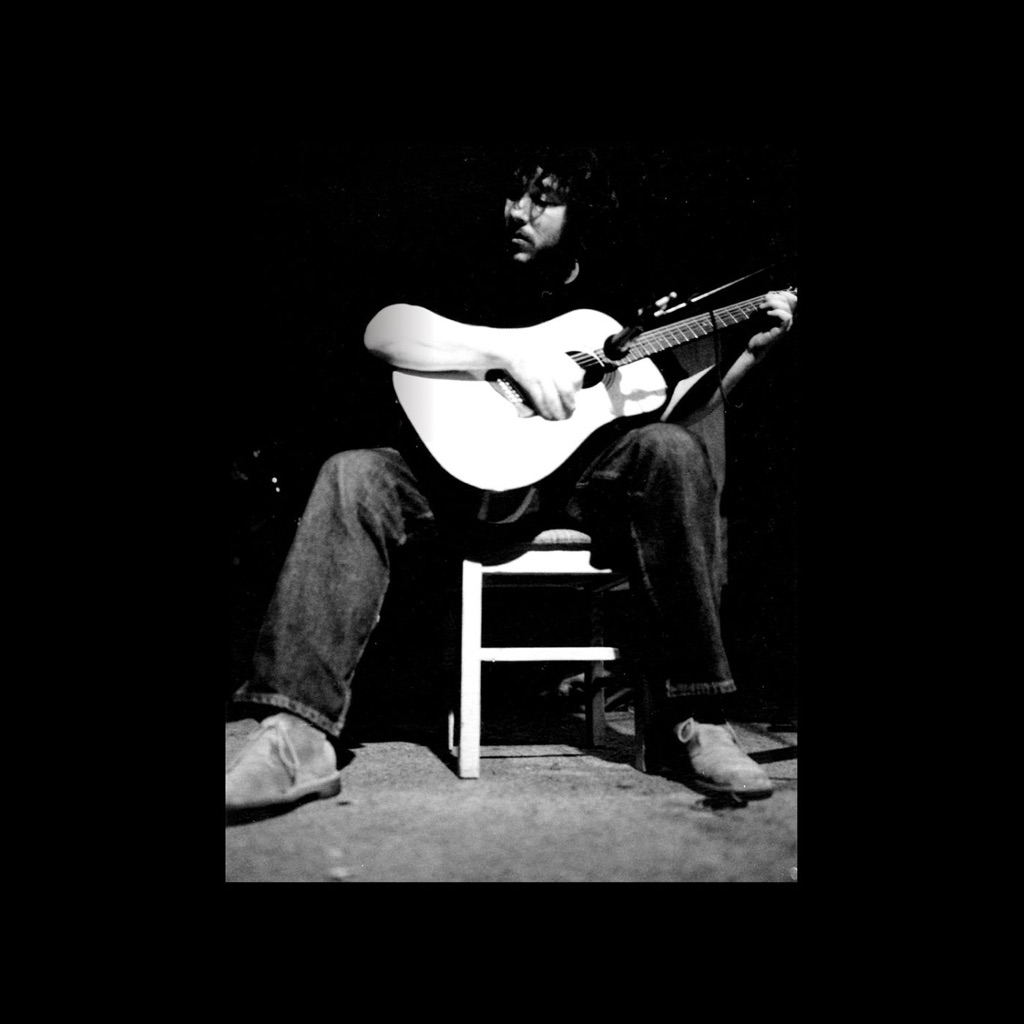

8.7 "Best New Reissue" on Pitchfork. "...the quintessential Rose album: gorgeous, inspired, and deeply confrontational." -- John Coltrane died at age 40, and in retrospect it seems as if the intensity of activity in his last years, the sheer torrent of notes, was an attempt at purging the music from his soul before it was too late. The guitarist Jack Rose died at 38, in 2009, and listening back to his catalog one has a similar notion. Like Coltrane, Jack Rose’s last years were marked by a shimmering intensity, an outpouring of his spirit, onto audiences and records. I believe Jack Rose felt the duty of preservation but was by no means bound by it. With his virtuoso fingerstyle technique and restless guitar explorations--modal epics, bottleneck laments, uptempo rags--it’s easy to hear a connection to tradition and at the same time a pulsing modernism: “Ancient to the Future” in the words of Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. Ultimately, it’s no use attempting to explain the unexplainable (natural disasters, God, art, death). As the air gets heavy before a thunderstorm, Jack Rose’s vivid guitar picking awakes in us a peculiar awareness, something ancient and American. Jack Rose’s work exists along the established continuum of American vernacular music: gospel, early jazz, folk, country blues and up through the post-1960s “American primitive” family tree from John Fahey and Robbie Basho and outward to other idiosyncratic American musicians like Albert Ayler, the No-Neck Blues Band, Captain Beefheart and Cecil Taylor. His process can best be heard as an evolution; renditions of songs would transform over time, worked out live, with changes in duration, tempo or attack, in the search for a song’s essence. “I Do Play Rock and Roll,” the title a mystifying nod to Mississippi Fred McDowell’s electric period, finds Jack Rose in extended drone mode, coaxing open-tuned raga meditations from his 12-string guitar. “Calais to Dover” first appeared on Rose’s classic “Kensington Blues” in a somewhat truncated form. The version heard here is more expansive and open-hearted, a waxing-and-waning piece of introspection. “Cathedral et Chartres” shares the same quiet romanticism, with rotating patterns and the chime of open strings, “Sundogs,” the sidelong drone abstraction that occupies Side B, stands alone among Jack’s solo work. A long-form live rendition of a track that appeared on the genre-defining triple album compilation “By The Fruits You Shall Know The Roots,” it is perhaps most evocative of Pelt, Jack’s previous band, a minor-key free drone, with only miniscule dynamic shifts and the occasional recognizable string accent. It is territory Rose seldom traveled but completely and fully invigorating. Jack Rose was a larger than life man with a hearty spirit--a no-bullshit gentleman--and his death continues to reverberate among the community of musicians and music people he called friends. This spirit, as evidenced within his recorded output, has proven to be indomitable and continually vital. -Scott McDowell, May 2016-