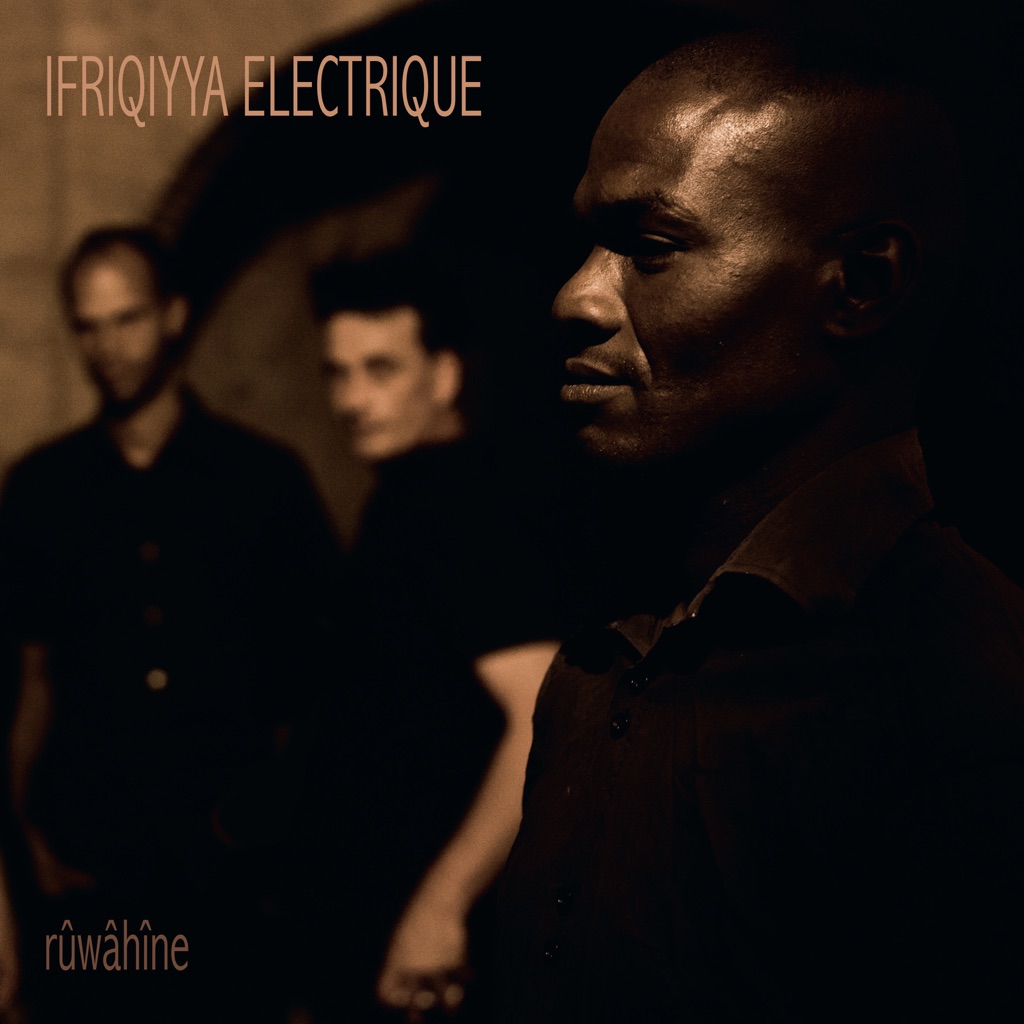

Rûwâhîne

Sufi trance musicians and rituals – from the depths of the Tunisian desert – in conversation with post-industrial sonics. ‘No theatre or stage or audience. The rûwâhîne have possessed and contorted the bodies of the Banga. Teenagers leap to the floor, their legs arched and tense, glaring transfixed [while] girls dance wildly, … accelerating the rhythm of the hand percussion’ The film opens on a cloud-pressed, bleached-out desert highway and an ominous electronic pulse, a devil of a wind, that you don’t want to shake off. Where are you? The truck in front carries human freight, half-glimpsed, anxious and thoughtful. You’re soon joined by the kind of dark lunar soundscapes familiar from Can, by polyrhythms at once deft and relentless, and then, as the truck reaches the outskirts of the town, by chants that seem to issue from the empty streets themselves. Ifriqiyah was the medieval entity that contained present-day Tunisia, as well as parts of Algeria and Libya: the boundaries, more or less, of the Roman province of Africa. Is this where you are? To get your bearings, you might first have to dive into a basement club somewhere in Southern Europe: Barcelona, perhaps, or Taranto or Palermo. For Ifriqiyya Electrique’s François Cambuzat – a guitarist and field recordist (Turkey, China, Central Asia) – is a veteran of the Mediterranean punk and avant-rock scene, which has always been more politically charged than its counterparts to the north and (far) west. With bassist Gianna Greco, he is one half of Putan Club – or one third when these two fierce and uncompromising players are joined by legend of the NY underground, Lydia Lunch. These are not spaces of comfort but of challenge and confrontation. But let us pull focus again – and this is crucial, bass and guitar and electronics notwithstanding. Ifriqiyya Electrique was formed in the Djerid Desert in southern Tunisia, home to the Banga ritual of Sidi Marzûq. The Banga is a key annual event in the lives of the black communities of the oasis towns of southern Tunisia, descendants of the Hausa slaves transported from sub-Saharan Africa. It is a ritual of adorcism not of exorcism: of accommodating the possessing spirit rather than expelling it. The invitation has been issued by the rûwâhîne themselves, the spirits from whom the record borrows its title, and is taken up primarily in the streets and in private houses. The Banga is a musical tradition for sure, with stark, metallic, cavernous percussion and voices of cool urgency, but should not be felt as such, for it is most defiantly a ritual and remains so on this record. Cambuzat and Greco are joined in live performance by the voices, krakebs and Tunisian tablas of three members of the Banga community, Tarek Sultan, Yahia Chouchen and Youssef Ghazala, with a fourth, Ali Chouchen, providing vocals and nagharat on the record itself. The voices and rhythms are unaltered, of course. What is new here is the conversation the group initiates between guitar, bass and electronics and the rhythms and chants of the Banga – what Cambuzat refers to a post-industrial ceremony. It won’t be an easy listen for purists and propagandists; but if post-industrial ceremony doesn’t describe a large portion of the most challenging music of the last 40 years, what does? In short, the music can only be fully understood in the context of the events that gave rise to it. Happily, Ifriqiyya Electrique is a film and documentary project as much as a band. The footage is astonishing: of wild, ecstatic gatherings that seem, to us, the un-initiates, by turns other-worldly and utterly familiar. It is familiar because we all recognise the need for “new ways of forgetting”, in Cambuzat’s words. But we surely need to remember too. For here is another deep tradition, another precarious music, on the brink: a vital part of a Sufi culture being pressed on all sides by the forces of reaction. Ifriqiyya Electrique will not be lamenting its passing – because they will refuse to let it pass. ‘This is, then, most certainly not a “world music” project (still less an ethnomusicological one), but a wild process of improvisation and re-composition that brings traditional instruments face to face with computers and electric guitars… [My work] is driven towards elevation, sweat, blood, poetry and tears – not to some pretty colour postcard’ — François R. Cambuzat / Ifriqiyya Electrique