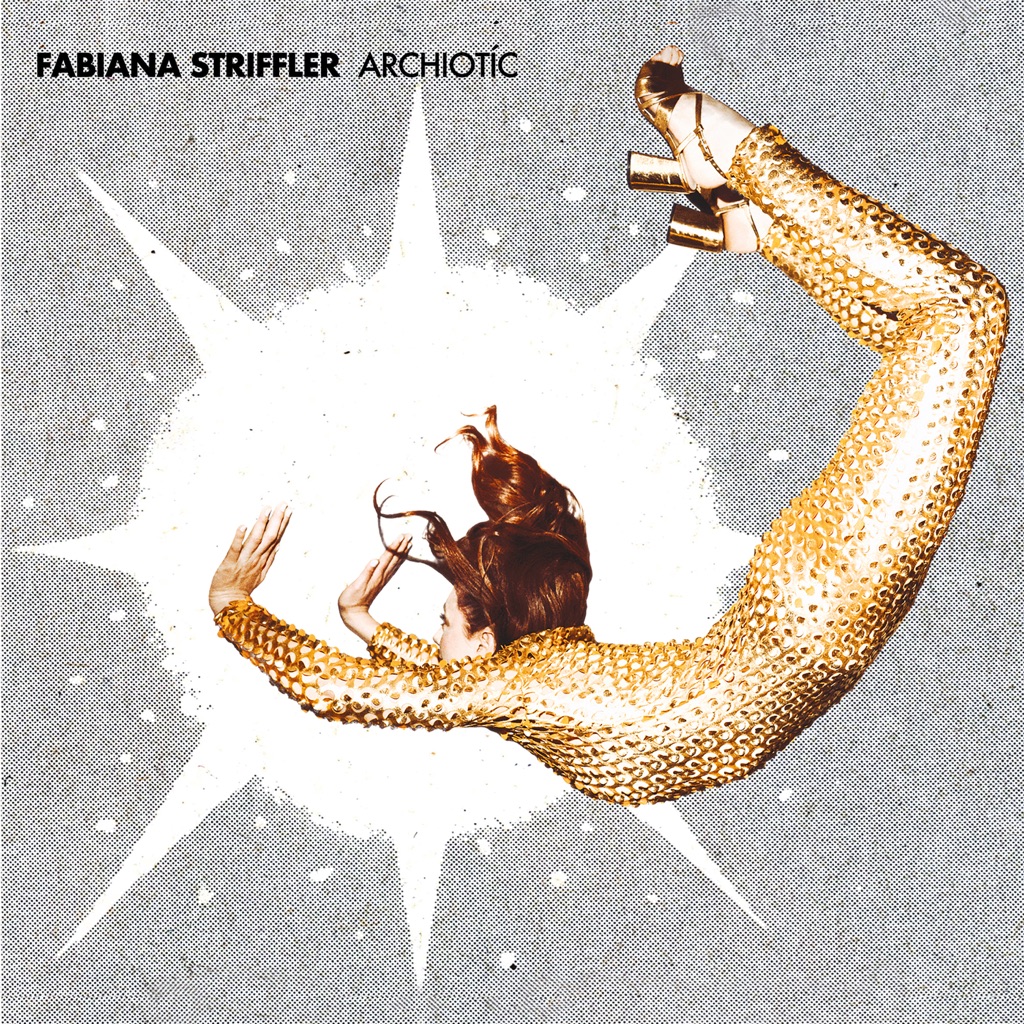

Archiotíc

Around three years ago Fabiana Striffler amazed audiences and media with her album Sweet And So Solitary. The magazine Jazzpodium devoted a double page to the violinist and composer from Berlin, calling her music a "fascinating cosmos of sound," while Deutschlandfunk concluded: "Fabiana Striffler's entire album is unconventional, sometimes even demanding and stubborn." Concerto magazine found that "Gustav Mahler might compose such songs if a time machine had catapulted him into the early 21st century: mysteriously radiant, touching and full of unheard sounds." And even in England Striffler received great resonance, for example in Hifi Critic: "It takes great skill to make something sound so profound and so grotesque at the same time." The current work builds on the predecessor in parts, but in many respects Fabiana Striffler also goes in other directions. More consistently than ever, she crosses stylistic boundaries and allows virtuosity and humor to intertwine in her composition and performance in a way rarely heard before. The newly assembled band of outstanding and immensely flexible musicians makes a substantial contribution to this. Striffler's multi-faceted violin playing and the no less free-spirited cellist Julia BiÅ‚at (Stegreif Orchester and others), with whom Striffler has been working since 2017, suggest occasional references to modernists of European classical music (Stravinsky, Bartók). The keyboard player Jörg Hochapfel has been known for years for odd surprises with his unconventional wit in the genre-busting Andromeda Mega Express Orchestra, furthermore he is considered an extremely sensitive accompanist - he shows both talents in Striffler's band as well. Max Andrzejewski and Paul Santner are among the most striking personalities of the contemporary jazz that is open in many directions, for which the Berlin scene is known throughout Europe. Finally, Striffler's long-term partner Greg Cohen (Tom Waits, John Zorn and others) left significant traces on the album, especially as producer. There is a clear stance in Striffler's compositions; one could also say a philosophical message. "I want to create something that opens people's minds. In Corona times, the phenomenon of people avoiding each other has increased even more. Already existing fears, for example of confrontation and loss, of the unknown and of different thoughts, were intensified by the real risk of contagion. With my music, I try to create a platform where people can let go. And I want to counter the trend of alienation and anonymization with something personal." The fact that - unlike in the past - there is no singing on Archiotíc was not initially planned by Fabiana Striffler. But then an instrumental concept turned out to be much more fitting. "It seems to me that the purely instrumental album better suits these times of overabundance of information. I wanted to make something that leaves more freedom to inspire one's own thoughts." The variety of timbres is enormous even without voices, as is the expansiveness and suggestive power of Striffler's pieces. The album's sweet opener, “Maraschino Cherries”, seems to melodically balance between circus and Italo-pop (Striffler spent her childhood in Italy); with a charming smile it brings together jazz bass grooves, bizarre synth chirping and violin pizzicati. The following “Chant Of The Earth” also lures with a catchy leitmotif, but clearly tends towards Anglo-American folk traditions. The deliberate sequencing of repetitions of the theme criticizes the monotony of advertising and radio and reverses their intention: "Repetition can also mean to get completely involved in something and to focus. ‘Chant Of The Earth’ is meant to be an appeal to listen to the earth," Striffler explains, "that's why there are the two reprises. The first tells, by means of an unusual contrabass guitar, what the planet looked like before we existed. And the second depicts the impact of humans on the world: Beauty and metal junk." The baroque box organ heard in the ending of “Chant Of The Earth” also plays a role in the immediately following key work of the album, “Invitation To Sin”. "This is my version of Genesis. The piece describes the moment when Man ate from the Tree of Knowledge, learned to reflect and was thrown back on himself in all nakedness," Striffler says. The parts of the violin, cello and organ represent Eve, Adam and the serpent, while the somewhat errant piano stands for the disorientation after the Fall of Man and the Expulsion. "When composing, I broke away from traditional music theory and instead was guided by the unerringness of intuition and twelve-tone music. At times the piece is even atonal, yet it doesn't sound dissonant." In the end of the album, “Memorandum Of Sin” picks up the thread once again. "Here I reflect on our need for physical nearness and tenderness in times of isolation through Corona. When it felt like a sin to get too close to another human being." Written for solo box organ played three-handed, “Memorandum Of Sin” figures as "an amputated duo that is unable to touch each other." “Dance Of The Elves” sounds exactly as one imagines the music to this title - a bit dreamy, at first also delicate, then infused with a magical power that culminates in jazzy interplay. The album's title track, with its South American groove, reveling pop and romance flirtations, and intentionally nostalgic sound, takes listeners to imaginary coffeehouses or bars of a bygone era. Similarly effectively, although much darker in mood, “Enchanted Woods” (very much in the spirit of Ennio Morricone) also creates the impression of a mysterious soundtrack for which the corresponding scenes are still to be shot. The next contrast follows directly when “Dreamy Back Roads” takes us to the USA of the founding era, where the horn of a locomotive, a folk fiddle and a growling bass reveal Striffler's affinity for bluegrass and Americana. Overall, Fabiana Striffler says her compositions are now much clearer than before. "I notated quite extensively, but left white spaces in between, where I relied on the intuition of others. The focus was always on message and feeling." Striffler also gets impassioned when it comes to manipulation through our increasingly digitized environment. "It's a paradox - algorithms suggest to us that we need what is similar to us. But what's the point? If there is no longer anyone I can have discussions with because everyone has the same opinion as I do, everyone likes the same music as I do, everyone wants the same objects as I do, there is no longer any impulse to think about new things. I am inspired by people who are completely different than me. That's exactly what you can hear on the album. It's not for purists, but for people who want to embrace something new."