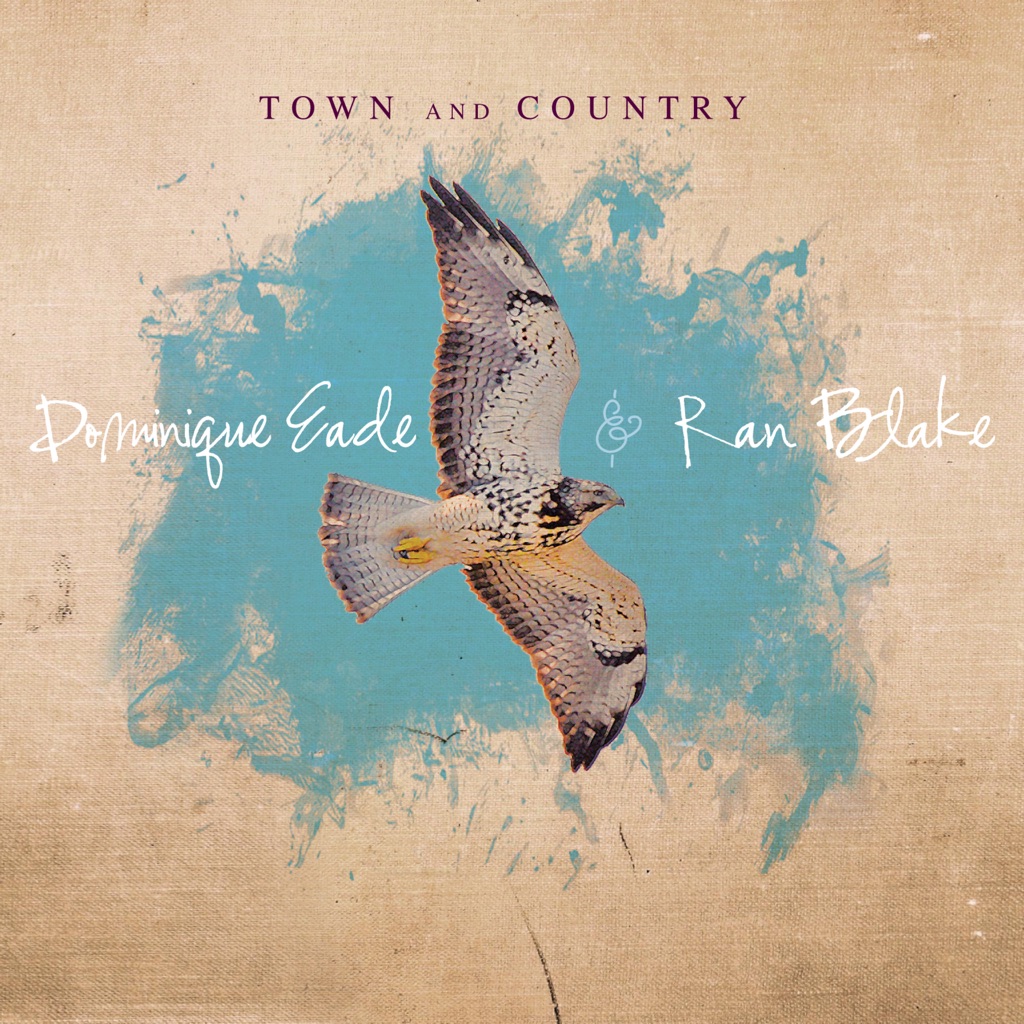

Town & Country

Singing a melody in key while pianist Ran Blake departs not just from the chords but the whole harmonic universe of the song: This is difficult. Vocalist Dominique Eade has the ears not just to stay with Blake, but to respond in kind to his enigmatic and painterly approach. Interpreting material from Lead Belly to Johnny Cash, Mahalia Jackson to Charles Ives, Eade and Blake grapple with the legacy of folk protest music in a set of stark beauty and immense power.

CD Quality - 16 bit / 44.1 khz Plainspoken but poetic, timely and timeless, poignant yet pointed: the American folk song tradition has a long history of confronting specific injustices while embracing a universal humanity. On the starkly moving Town and Country (out June 9 on Sunnyside), vocalist Dominique Eade and pianist Ran Blake take the long view of our own tumultuous moment in history with a wide-ranging collection of folk tunes that examine the travails of Americans from Main Street to the mountains. With the varied repertoire on Town and Country, Eade and Blake – long-time colleagues both on the stage and as educators at Boston’s New England Conservatory – present a broad notion of folk song that’s as diverse as the nation itself. There are the expected classic tunes and country ballads, the ill-fated coalminers, the tragic romantics grasping out their last breaths, the cries of faith and determination sent heavenward. But in the agile imaginations of these two inventive artists, who share a love for skewing the traditional through a modernist lens, the folk idea is broad enough to include film noir laments and TV-scaled road songs, moonlit love and Third Stream austerity. “During the election season I was thinking a lot about the planet,” Eade explains. “Usually Ran and I draw material from the Great American Songbook because we both have a love for that, but in this case I really wanted to say something different. Many of these folk songs deal with things like the prison system and poverty and wealth disparity, different parts of our country coming through this music. The nature of folk music is that there’s a lot of history in the words, but that history felt very relevant to making a statement in and of our time.” The material here ranges from Bob Dylan’s scathing attack on consumer culture, “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” to “Give My Love to Rose,” Johnny Cash’s bitter ode to those abandoned by the prison system; Charles Ives’ poetic portrait of “Thoreau,” the founding father of the New England Transcendentalists, to a pair of shadow-shrouded nursery rhymes (“Lullaby” and “Pretty Fly”) from Charles Laughton’s children-in-peril noir classic The Night of the Hunter; the English lynching protest “The Easter Tree,” which presages Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit,” to the gospel plea of “Elijah Rock,” best known from Mahalia Jackson’s unforgettable rendition. All these songs are unified and transformed by Eade and Blake’s stunning treatments, which render them all with unvarnished lyrical force combined with strikingly unique harmonies, unpredictable phrasing and evocative atmospheres. Though Town and Country is only the duo’s second recording together – following Whirlpool from 2011 – it reveals a singular, focused chemistry forged over decades of playing together. The two met in 1978 when Eade arrived in Boston to study at Berklee – until she heard Blake, then the chair of the Contemporary Improvisation Department (known at the time as the Third Stream Department) at New England Conservatory where he’s still on faculty. The encounter proved life-changing for the young singer. “Ran’s solo playing seemed to me like an inevitable extension of Thelonious Monk, who I adored,” Eade recalls. “That’s when I decided to switch and study at NEC.” Blake was equally impressed with Eade’s expansive talents. “Dominique is one of our great singers, composers and teachers,” he says. “Her range is fabulous and her ears pick up amazing subtleties. Her repertoire ranges from Stan Kenton to coal miner songs to English folk songs, and she has a keen sense of pulse with bebop scat, political protest, and the forgotten standards. It felt so natural performing with her.” Gunther Schuller, then president of NEC, founded the school’s Jazz Studies Department in 1967 and invited Ran to chair the new Third Stream Department two years later, passing the great composer’s teachings regarding the merger between classical and jazz on to students like Eade. The duo pays tribute to Blake’s, and by extension Eade’s, mentor on “Gunther,” which is an improvisation on a 12-tone row composed by Schuller. Blake takes solo turns with “Moti” and the two versions of “Harvest at Massachusetts General Hospital,” representing his distinctly acute harmonic approach. Much of the repertoire was suggested by Eade, who began her life in music as a singer-songwriter, only shifting her focus to jazz in her early college years at Vassar. “I was looking for a way to connect the music that I was performing in high school to modern jazz, which I was quickly falling I love with,” she says. “Everything changed when I heard Miles Davis’ Nefertiti for the first time, or whatever the other soundtracks to my college years: Keith Jarrett’s Belonging, or Roland Kirk’s Rip, Rig and Panic. It’s a tall order to meld that with all the other things I was into, but I guess that’s why I’m still at it.” Blake made key additions to the program, however: the two Night of the Hunter songs continue his long-running dedication to film noir (his department at NEC presents an annual live soundtrack to a noir film), the three “moon” standards (“Moonlight in Vermont,” “Moon River” and “Moonglow,” the latter paired with the theme from Picnic, in which it appears) were his suggestion, as was the Dylan song, its verbal avalanche given a tour de force performance brimming with urgency and righteous anger. “This music feels like a journey through different parts of U.S. history and geography,” Eade says. “I felt more like Ran and I were a couple of vagabonds rummaging through a shared history, both of our own and of wherever we happened to be in the world.”