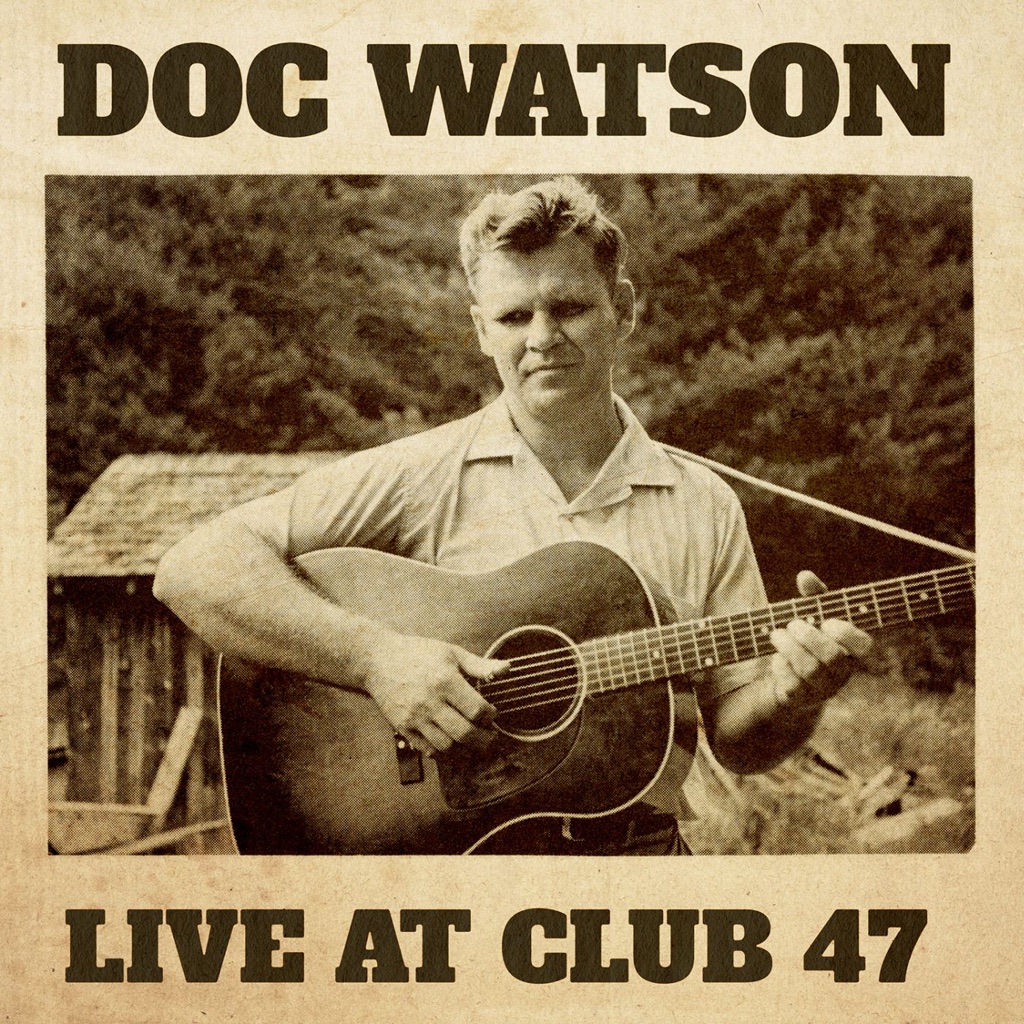

Live at Club 47

Doc Watson Live at Club 47 The year 1958 was a seminal turning point for the coming resurgence of American folk music. Three young college kids who called themselves The Kingston Trio had a hit record that year with an old folk song from the North Carolina hills, “Tom Dooley,” which went to Number One on the charts and sold over three million singles. One result of that record’s success was that college kids across America went out and bought banjos and guitars and tried to learn to play them in an attempt to impress their friends. Another result was that three important folk music clubs, each of which made a huge contribution to what would become the “folk revival” of the mid-1960s, opened their doors for the first time in 1958. In Los Angeles, the Ash Grove became the community center for traditional music and musicians, while across the country in New York, the Gaslight Cafe on MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village was the headquarters for that city’s folk revival. In Cambridge, MA, it was the Club 47. Two enthusiastic music fans, Joyce Kalina and Paula Kelley, opened the Club 47 (named for its address, 47 Palmer Street) in Harvard Square in Cambridge in 1958. Early bookings were primarily blues and jazz, and drew enthusiastic audiences of college kids. The bill of fare gradually expanded to include traditional folk music, bluegrass, and eventually singer-songwriter folk. A young Joan Baez, then a student at Boston University, began playing there in late 1958 on Tuesday nights, when the jazz musicians who usually held forth had the night off. And soon the club began to book touring folk music artists from across the country; enter Doc Watson. Long acknowledged as America’s premier folk guitarist, Arthel Lane “Doc” Watson was born in what was then the tiny rural community of Deep Gap, North Carolina in the heart of the Blue Ridge mountains on March 3, 1923. Although a total of nine children were born to General Dixon Watson and Annie Greene, Arthel was different; he lost his eyesight in early infancy. All the Watsons were either proficient or at least casual musicians or singers, and several generations of the family had lived in the area where, although poor in material goods, they were rich in their familiarity with and knowledge of local folklore, including the true story of the fatal triangle of Tom Dula, Laura Foster and Ann Melton that formed the basis of the aforementioned hit song “Tom Dooley.” Surrounded by music and musicians, Doc and his siblings grew up listening to hymns, murder ballads and down home string band music, all of which would later find places in his own repertoire. The old fashioned radio and the family Victrola played 78s by Riley Puckett (another blind guitarist, Puckett would find fame as a member of Gid Tanner’s Skillet Lickers), Charlie Poole, Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family. Music was always a part of Doc’s life; from earliest childhood, each Christmas he’d find a small harmonica tucked into his stocking, and at age seven he got his first stringed instrument, an old banjo, from his father. Doc recalled: “I started playing the guitar a little when my first cousin left his guitar at our house. Also, I had learned a few chords from an old boy at the Raleigh School for the Blind. I was messing with my cousin’s guitar one morning before my dad went to work, and he turned around to me after he finished his breakfast and said, ‘Now son, if you learn to play just one little tune on that by the time I get back, we’ll go to town Saturday and buy you a guitar.’ Well, I knew I had him right there, because I knew almost enough already to play a song, and I knew that I could be singing along with my playing by the time he got back. The first song I learned on the guitar was “When The Roses Bloom in Dixieland” by the Carter Family. My dad was just as good as his word. We went to town and found me a little guitar. It was one of the ten dollar guitars – a pretty good little thing to learn on, but as hard to fret as a barbed wire fence. A few years later, when I was sixteen or seventeen, I earned enough money from cutting down some dead chestnut timber (used for tanning leather) to order a guitar from Sears and Roebuck.” Several well known Southern guitarists were blind. Reverend Gary Davis, Blind Willie McTell, Riley Puckett, Blind Boy Fuller and Blind Willie Johnson were just a few of the musicians whose lack of sight was directly responsible for their musical careers. Doc once said of his own blindness, “If I hadn’t been handicapped, I probably would have been a mechanic or an electrician or something like that, so I could go home at night. Music would have been a hobby. I won’t say that I wouldn’t have picked a guitar, but I wouldn’t have made a profession out of it. And if it hadn’t been for my dad putting me on the other end of a crosscut saw and teaching me that I was of some benefit other than to just sit around in the corner somewhere, I don’t think I would have had much incentive in life to do anything. My dad taught me that just because I was blind, that didn’t mean I was helpless.” In 1946 Doc married his young neighbor Rosa Lee Carlton, the daughter of another local old time music legend, fiddler Gaither Carlton. Doc and Rosa Lee had two children, son Eddy Merle (named after country music legends Eddy Arnold and Merle Travis), born in 1949, and daughter Nancy Ellen, born in 1951. And true to his father’s teaching, the word helpless had no place in Doc’s lexicon; in 1957 he did the complete electrical wiring in the first home he and Rosa Lee owned. His work passed the stringent inspection by the state, and was written up in the electric company’s monthly newsletter. Doc continued to play music on weekends for local dances in the area, and in 1953 formed a honky-tonk dance band with pianist Jack Williams called Jack Williams and his Country Gentlemen. Their repertoire consisted primarily of rockabilly, country and western, pop standards and square dance tunes, and Doc played electric guitar in this ensemble. To fill occasional square dance requests, Doc learned to flatpick fiddle tunes on the guitar, as Joe Maphis had done in the 1930s. Unlike his contemporaries Chet Atkins and Merle Travis, who started their professional careers playing acoustic guitars and later switched to electric, Doc began on electric and later made the transition to acoustic with the advent of the folk revival of the Sixties. Although he continued to work with Williams playing country and pop music, Doc never stopped playing traditional mountain music with his family and friends at home. These included Clarence “Tom” Ashley, Doc’s father-in-law Gaither Carlton, and two other neighbors, fiddler Fred Price and guitarist Clint Howard, all of whom would travel and record with Doc in the future. It was in these comfortable home surroundings that Doc was first discovered and recorded by folklorist Ralph Rinzler and collector and discographer Eugene Earle, who were on a collecting trip through North Carolina looking for traditional artists to record. Once these field recordings were released, as “Old Time Music at Clarence Ashley’s Vol. 1” (and later Vol. 2) on Folkways Records, Doc’s reputation grew, and he soon began playing for enthusiastic urban audiences farther from home. Rinzler presented Doc in concert in New York City for his organization, The Friends of Old Time Music, in March of 1961, and booked a series of follow up dates which included a stop in Cambridge at the Club 47 in February of 1963, where the present recordings were made. In the book Baby Let Me Follow You Down, by Eric Von Schmidt and Jim Rooney (University of Massachusetts Press, second edition, 1994), Ralph Rinzler talks about bringing Doc Watson to Cambridge for the first time. “Cambridge was very fertile turf. When I was trying to get Doc Watson started, it seemed right to go there as frequently as possible. People there really got into Doc as a person, whereas in New York he was always treated as a phenomenon who played hot licks. You didn’t really have any human interchange there. It was like taking a bath in humanity when you’d come up to Cambridge. I really thought that our visits there were an extraordinary experience. And so did Doc.” “Wabash Cannonball” Doc cites the Carter Family as his source for this song; he may also have heard Roy Acuff’s early version, recorded for Vocalion on October 21, 1936, or that of the Delmore Brothers, whose Bluebird recording was done on February 6, 1940. “The House Carpenter Doc” mentions hearing his father sing this ballad, but it’s clear that he also heard it from his friend and neighbor Clarence Ashley, who had recorded it for Columbia as long ago as April 14, 1930. Ashley and most others who performed this song accompanied themselves on banjo. “I Wish I Was Single Again “and “Little Darling Pal of Mine” are both well-known Carter Family songs. “Train That Carried My Girl from Town” and “Worried Blues” were two sides of the same 78, recorded by Frank Hutchison at his very first session for Okeh on September 28, 1926. “Old Dan Tucker,” Doc learned this song from a 78 by Gid Tanner & the Skillet Lickers, featuring legendary guitarist Riley Puckett, who recorded it for Columbia in 1928. “Sweet Heaven When I Die” although Doc mentions a recording by Dick Hartmann and the Tennessee Ramblers as his source for this song, it’s possible that he heard them perform it on the radio, as there’s no indication that they ever actually recorded it. It’s also possible that he misremembered his source and actually learned the song from the 78 by the Tenneva Ramblers, or from the Carter Family, who recorded a variant called “Sweet Heaven in My View” for Decca in 1936. “Talking Blues,” written and recorded by Chris Bouchillon in 1927, this song is popularly credited with originating the “talking blues” format later used by Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan, among others. “Little Margaret” Doc switches from guitar to banjo for this ballad, which he learned from a recording by Pete Seeger. “Sitting On Top of the World” was learned by Doc from the recording by the Mississippi Sheiks. “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” Charlie Poole recorded this song in at his first session for Columbia in 1925, and it traveled widely; artists as diverse as Bob Dylan and Flatt & Scruggs, among many others, have recorded versions of it. “Blue Smoke” is a Merle Travis-penned instrumental that shows off Doc’s guitar playing virtuosity in fine style. “Deep River Blues” the Delmore Brothers were Doc’s source for this, probably his most-copied song. “Way Downtown,” “Somebody Touched Me” and “Billy in the Low Ground,” Doc is joined onstage for these three traditional songs by Ralph Rinzler on mandolin and John Herald on second guitar and both men on harmony vocals. In addition to being a folklorist, Rinzler was for a time a professional bluegrass musician, and was a member of the Greenbriar Boys with Herald. “Boil Them Cabbage Down” Doc probably learned this song from the 1924 version by Fiddlin’ John Carson, although it was a staple in many repertoires and was also recorded in the 1920s and 1930s by Uncle Dave Macon, Gid Tanner, Earl Johnson, the Crockett Family and Clayton McMichen. “Everyday Dirt,” Dave McCarn wrote and recorded this song at his first session for Victor in 1930. “I Am a Pilgrim” learned from the playing of Merle Travis. “No Telephone in Heaven,” Doc plays this old Carter Family song on the autoharp. “Hop High Ladies the Cake’s All Dough,” another one from the singing of Uncle Dave Macon, who recorded it in 1927. “Little Sadie,” Clarence “Tom” Ashley first recorded this for Columbia on October 23, 1929, and Doc heard him playing it many times during their long friendship. “Black Mountain Rag” and “Blackberry Rag” are Doc’s versions of old fiddle tunes that date to the mid-1920s, the latter from Fiddling Arthur Smith. John Herald returns on second guitar. “Days of My Childhood” plays is a sentimental song that comes from the repertoire of blind singer Alfred G. Karnes. Shortly after these recordings were made, Doc’s career began expanding rapidly. Following his success at the Club 47, Rinzler booked him to appear at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival along with Fred Price and Clint Howard; the live recordings made there, along with his subsequent 1964 debut solo album for Vanguard Records, brought him national attention and acclaim. Generations of puzzled guitar players would sit in front of their stereo speakers, trying to figure out the chord changes to “Deep River Blues,” with varying degrees of success. Rinzler then introduced Doc to the family who would be his managers and booking agents for the rest of his life, Manny and Mitch Greenhill of Folklore Productions. After Manny’s death in 1996 his son Mitch, who had already produced several of Doc’s albums, took his father’s place as Doc’s booking agent and manager. Under the faithful stewardship of the Greenhills, Doc enjoyed a comfortable recording and performing career, during which he would earn seven Grammy Awards and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences. In 1997 he was presented with the National Medal of Arts at the White House by then-President Bill Clinton, who introduced him by saying, “There may not be a serious, committed baby boomer alive who didn’t spend at least some of his or her youth trying to learn to pick a guitar like Doc Watson.” Although they are not present on these recordings, mention must be made of three musicians who were part of Doc’s signature sound for most of his career. His son Merle Watson, who had been taught to play guitar by his mother during the long months when Doc was on the road, acted as second guitarist and road companion to his father until 1985, when Merle was tragically killed in a tractor accident. In his memory Doc established Merlefest, a musical celebration of Merle’s life which has grown to become one of the premier roots music festivals in the country. In 1983 Merle had hired his friend Jack Lawrence to make occasional appearances with Doc when Merle was unable to perform, and Jack joined Doc full time as second guitarist after Merle’s death. In 1998 Doc did a public television special with musician and storyteller David Holt, and that sparked interest in the duo. They began performing together late that year, both with and without Jack Lawrence, and were on the road together until Doc’s death. Doc often said that without Merle, Jack and David he could not have toured as comfortably or as much as he did, had it not been for their musical and personal assistance. Doc’s final live performance was, fittingly, at Merlefest, on April 29, 2012 as part of a gospel session with the Nashville Bluegrass Band. He died a month later, after a short illness, on May 29, 2012, at age 89. Mary Katherine Aldin September 2017