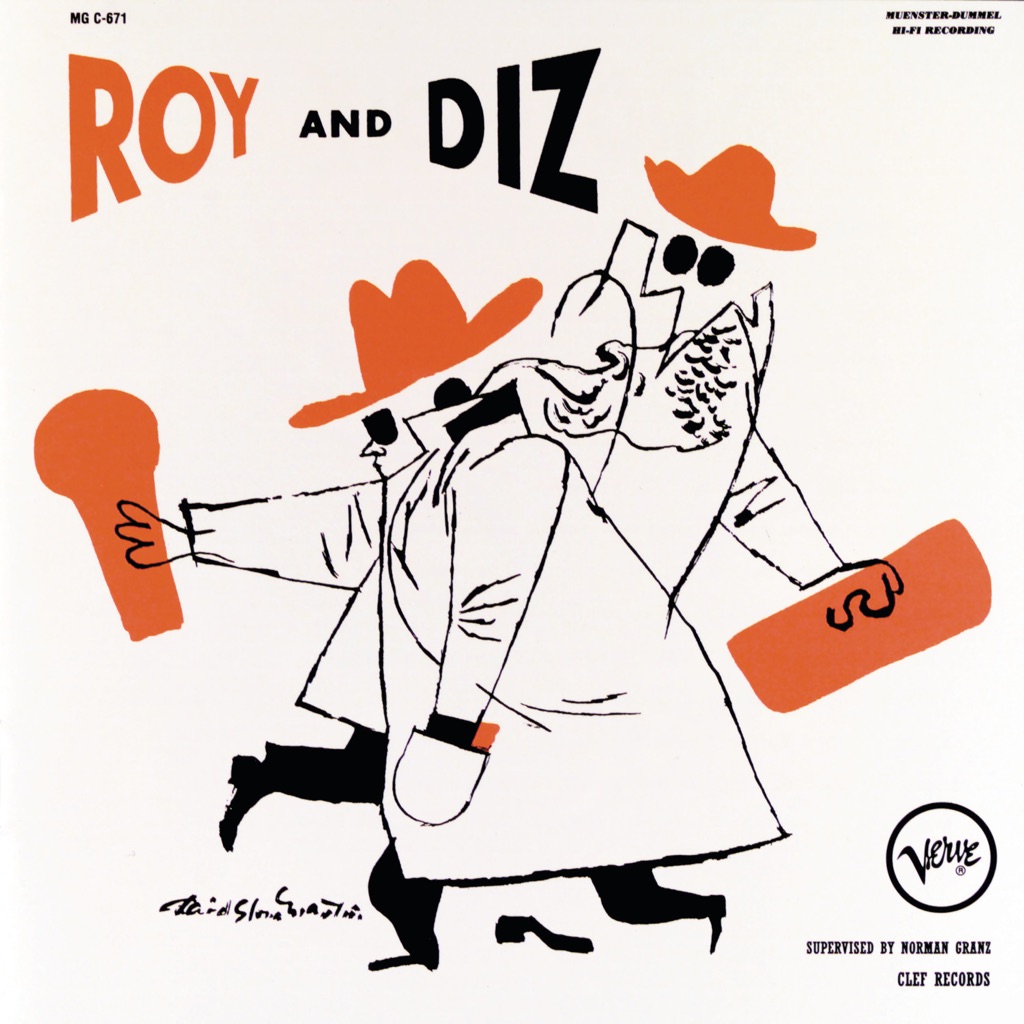

Roy and Diz

Given the proven appeal of his touring jam session Jazz at the Philharmonic, it made sense for producer Norman Granz to carry that ethic over to the studio, as he did in this 1954 trumpet summit for Clef Records (a precursor to Verve). *Roy and Diz* also carries on another JATP imperative, partnering the giants of the swing era with those of the bebop movement, rejecting the false choice of one against the other. Roy Eldridge was the most influential trumpet stylist after Louis Armstrong, and the first African American to appear as a featured soloist with a white band (the Gene Krupa Orchestra, in the early ’40s). Dizzy Gillespie was the intellectual driving force of bebop, a virtuoso without peer, the most influential trumpet stylist after Eldridge. Released alternatively as *The Trumpet Kings* and *Trumpet Battle*, *Roy and Diz* featured the two greats with pianist Oscar Peterson and his trio members Herb Ellis (guitar) and Ray Brown (bass), adding the versatile Louie Bellson on drums. Peterson’s combo functioned as a kind of house band for these star encounters: They’d recently also made *Lester Young With the Oscar Peterson Trio* and *Diz and Getz* (the latter featuring Gillespie’s bebop ally Max Roach on drums). The melodic interplay of Dizzy and Eldridge on “Sometimes I’m Happy,” “Blue Moon,” and the furious closer “Limehouse Blues” harks back in a way to the two-trumpet legacy of King Oliver and Louis Armstrong, who made some of the founding recorded documents of jazz. On these tunes one horn takes the main melody, the other creates what was called a “second” (i.e., a second part)—a response in counterpoint to add to the flow. Diz and Roy also both sing and scat on the novelty number “Pretty Eyed Baby,” keeping elements of the call-and-response approach in place and cutting loose with their own over-the-top vocal improvisations, deeply in the spirit of Armstrong as well. Both trumpets begin the session with mutes, creating a softer timbre and a more restrained feel (very much unlike Armstrong). But when those mutes come off on “I\'ve Found a New Baby” and the latter half of “Blue Moon,” both Diz and Roy demonstrate their playing-to-the-rafters lung power while losing none of their agility. Eldridge’s arcing phrases owe a debt to the language of tenor sax innovator Coleman Hawkins, a primary influence. Gillespie’s dazzlingly precise double-time lines embody all the ingenuity of the bop vernacular he perfected with Charlie Parker a decade before. Together the two engage in what is less a battle and more an expression of shared joy.